The hand went up slowly with its owner casting nervous glances around the darkened Church.

I was at a parish giving a talk on the Theology of the Body to a group of young people preparing for confirmation. I had just referenced our current cultural confusion on gender: 70+ gender options on Facebook; the U.N. debating treaties which would recognize over 100 genders as part of promoting human rights across the globe; the growing numbers of people who describe themselves as “gender fluid,” “nonbinary,” or “transgender.”

A hush fell over the Church as the young man asked his question: “but how many genders are there?” Both the high school students and the adult catechists leaned forward in their seats, seeming to hold their breath.

“Two,” I said, “scripture and science tell us there are only two: ‘male and female’” (see Gen. 1:27).

The Catholic Church’s Teaching on Gender

The Church does not teach that gender is multiple, fluid, changeable, and self-chosen. It does not believe that our bodies are a screen on which to perform or write an identity. Nor does it believe that this identity can be changed or altered at will like we can change a social media profile using medical technology to rewrite the body and its “sex assigned at birth.”

The Church does acknowledge “that ‘biological sex and the socio-cultural role of sex (gender) can be distinguished but not separated” (Pope Francis, Amoris Laetitia, no. 56). In other words, we can look at the way different cultures understand and live out what it means to be male or female. But when that is separated from our bodies and their actual physical sex, it goes off the rails. It doesn’t matter if we think that this wholly separate gender is imposed on us by our culture as did Simone de Beauvoir in the mid-20th century or that it is totally individual and self-articulated as some people do in the early 21st century. Because gender and sex are so connected, there can only be two.

Why? And why has the Church been warning us for decades about this gender ideology that dissolves the connection between gender and sex, denies that the body has any intrinsic meaning, and in so doing undermines both marriage and the family?

Because the body matters. That is both a pun and a profound metaphysical truth. Saint John Paul II taught us that we must understand our bodies through the lens of gift. They are part of God’s gift to us in creation. We are inescapably a unity of body and soul. Our bodies express the reality of who we are as persons—self-aware subjects possessed of a profound freedom. We are not just somethings; we are “someones”—and our bodies testify to this.

Our bodies also witness to our capacity to give ourselves as gifts. When we give our bodies, we give ourselves. This is true in marriage. It is true in celibacy and consecrated virginity. Chaste friendship outside of marriage also involves bodily giving—though not in a genital way. This is why, as Pope Francis has reminded us, that when we give ourselves sexually outside of the total covenantal commitment of marriage, we create wounds in our spirits.

Integral to our capacity to give ourselves in and through our bodies is their sex (or, in another sense, their gender). When we give our bodies, it is as a man or woman—whether in marriage, celibacy, or in committed friendship in the Body of Christ. The fact that God created us male and female means that our sex is always relational or, as John Paul II put it, spousal. In Genesis 2 the human creature whom God made (adam) only recognizes himself man (ish) when woman (issah) stands before him (see verse 23). He recognizes the meaning of his body in her and she in him. It is this which enables him to bind himself to her as his “bone and flesh” and to become “one flesh” with her in the mutual gift of their bodies (Gen. 2:24-25). This bodily gift in turn enables God to bless the union of the couple with the further gift of a child made in the image of God (see Gen. 1:28; 4:1).

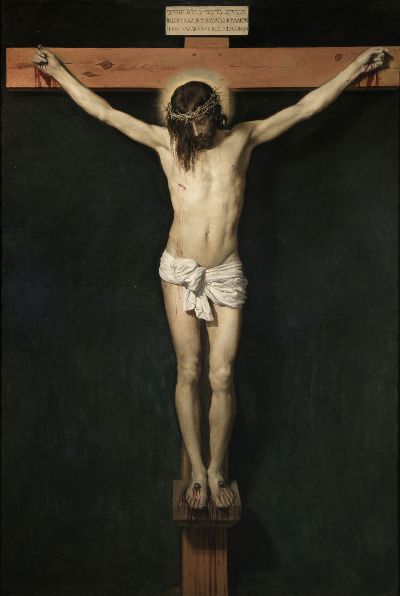

So, instead of viewing the body as a screen on which to project or perform an identity, the Church sees it as a window into the depth of the person who is inescapably male or female. We can think of the body as a compass which points us toward love—both the love which is our origin and the love which fulfills us. After all, “it is not good for the man to be alone” (Gen. 2:18). But to read this compass well and to navigate by it we need the “map” given to us by revelation because Christ “reveals man to himself and makes his supreme calling clear” (Vatican II, Gaudium et spes, no. 22). That calling is love. Christ is the Father’s eternal Word of love, spoken from all eternity; spoken in time in the Incarnation to lead us back to our Father.

How to Love Those Who Struggle With Gender

It is true that there are people who struggle with the pain of discordant gender identity or gender dysphoria (also known as gender identity disorder). For some this is something which persists from their childhood into adulthood. For others, it is something developed in adulthood after having their sense of self destabilized by exposure to gender ideology or to a peer group impacted by it (rapid onset gender dysphoria).

The Church’s teaching on the gift of the body and sexual difference makes clear why it is a tragic mistake to try reconfigure the bodies of those suffering from gender dysphoria through chemical and surgical procedures aimed at making their bodies look like those of the opposite sex. The sad truth is that these procedures do not—and cannot—change someone’s sex. Genetically the person retains their original sex. They must stay on cross sex hormones throughout their lives to try to continually override their body’s attempt to express its given biological reality. They will never be able to bear children as a member of the opposite sex because their fertility is destroyed by the transitioning process.

This teaching is corroborated by scientific and medical study of the impact of gender transitioning. In reality these procedures do not improve the physical or psychological health of those who undergo them. For example, rates of suicide among those who have fully transitioned are 19-20 times higher than the general population for those who have transitioned fully–even in ostensibly “trans-friendly” cultures. This should not surprise us as using harsh medical procedures to treat what is primarily a psychological condition makes little sense.

In addition to appropriate psychological support, what people struggling with discordant gender identity most need is love. Many of them are alienated from their families, feel socially outcast, and even experience rejection from people in the Church. This is wrong. The Catechism tells us that people who see themselves as part of sexual minorities deserve to be treated with “respect, compassion, and sensitivity” within society but particularly within the Body of Christ (see CCC, 2358—while this is said of people with same sex attraction, it is no less true of those with discordant gender identities).

But, let’s be honest. Love is the most basic ontological need that every human being has. It’s not that “they” need love. We—all of us–hunger, thirst, and yearn to be fully known and unconditionally loved. And all of us carry wounds within ourselves which are the scars of original sin, the sins of others, and our own sins. Some of these wounds affect and distort our sense of self. Some affect our desires. Even if our gender identity is not discordant, we all live in a culture deeply traumatized by the chaos of the sexual revolution. We all come from families marked by the Fall. We all fail and fall short in choosing to love authentically in and through our bodies.

Pope Francis reminds us that the Church is meant to be “a field hospital” and Christian families within it “the nearest hospital” (Amoris laetitia, no. 321). Hospitals are for the sick and the wounded. Field hospitals are set up near a battlefield to tend the causalities brought in from the fight. The battle for the soul of our age is being fought in great part on the terrain of sex and gender, marriage and family. This is just one part of the great spiritual battle that has raged throughout the Church’s history and the history of the world.

In the hospital which is the Church or the Christian community we encounter Christ who is the Great Physician. Like the Good Samaritan in the Gospel parable (Lk. 10:25-37), he tends our wounds with the medicine of his mercy and the balm of unconditional love which are poured out to us in the sacraments. He brings us back to our Father who loves us infinitely. He equips us with the power of the Holy Spirit so that we can help others among the wounded to encounter Christ our Healer.

To learn more about gender ideology, it’s impact in the world around us, where it comes from, and what scripture and Church offer us as a life-giving alternative to it, see my book Unraveling Gender: The Battle over Sexual Difference (Charlotte, NC: Tan, 2022). It is available at here (but not on Amazon).