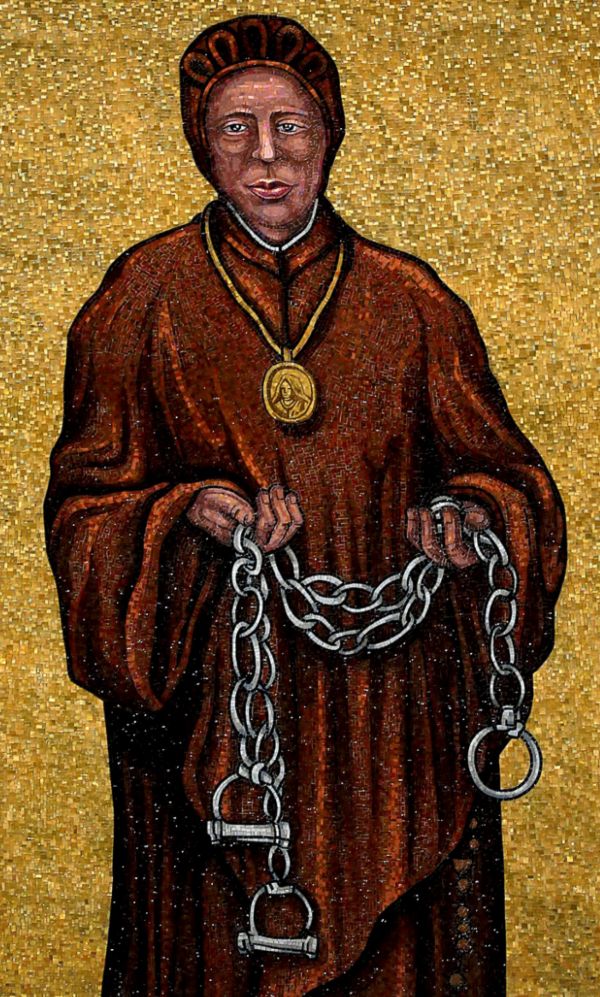

Few things say Italy like Venice. The vantage from any Venetian window might convey the smell of Italian cuisine, the bustle of a boisterous cityscape, or the sound of a string quartet propelled by a sun-tanned gondolier. Few things say Italy like Venice, but it’s quite common for non-Italians to grace the city’s busy streets. As a Mediterranean port city, Venice is a melting pot of culture, race, and custom. Thus, for many, the city constitutes their first experience of a new world. Such was the case for a young African slave woman who found herself working under a new “master” in a new city and an entirely different culture. Despite her new circumstances, this African girl would someday become a Venetian hero: Saint Josephine Bakhita.

Born in 19th century Sudan, Josephine Bakhita was the furthest thing from Italian. Her black skin revealed different ancestry and a different life experience. Hers was not the skin of an Italian aristocrat but rather a child kidnapped and forcibly relocated in the slave trade. Born around 1869 (though the exact date is unknown), Josephine lived a horrific life at the hands of at least four slave owners. For seven years, Josephine was passed like merchandise from one owner to the next. Still, the hands of providence eventually placed her under the roof of a relatively kind family: the Michielis. Josephine’s transfer to the Michielis would eventually lead to her permanent residence in Venice.

There, far away from her homeland, Bakhita acquired her freedom, converted to Christianity, and became a Canossian sister. She worked in service to the Lord until her death on February 8, 1947. At her canonization mass on October 1, 2000, Pope Saint John Paul II reflected on Josephine: “Abducted and sold into slavery at the tender age of seven, she suffered much at the hands of cruel masters. But she came to understand the profound truth that God, and not man, is the true Master of every human being, of every human life.”1

Josephine stood as a contrast to Venetian culture. When she arrived in Venice, she did not speak the language. Even after a formal education in the convent, she never adequately learned to read or write. She spent the majority of her childhood severely malnourished and endured frequent beatings. One might say that her life was burdened by disadvantage, but, in a mark characteristic of holy people, Josephine made a grace-filled choice to become a saint despite her difficult circumstances. While Josephine’s life offers many lessons, I would like to focus on five.

Lesson 1: Freedom

Many voices in contemporary culture want to convince us that there is no such thing as freedom. Whether in biology, psychological background, or culture, human beings have no freedom. Instead, humans are determined to act in specific ways by factors outside their control. Determinism makes life meaningless, and the Church has always opposed it. As is characteristic of most saints, Josephine’s life contradicts this lie of the culture—that we have no freedom to change the circumstances of our lives. Josephine rose above her difficult circumstances, utilizing her freedom to accept God’s grace.

Josephine’s circumstances were difficult indeed. As a child, Josephine’s abductors ambushed her, held a knife to her side, and whispered, “If you scream, you’re dead. Now come follow us.”2 After stealing Josephine, they forced her to walk barefoot for days, hid her in the dark for a month, and eventually sold her to her first “master.”3 As a teenager, Josephine’s body began to mature beautifully. Josephine’s slave master noticed. Not wanting her to cause any disruption amongst his slaves, he publicly and permanently disfigured her body to ensure that no one would find her attractive.4 Bakhita was beaten on many occasions, several times to the point of death,5 but perhaps none was so gruesome as when she received her “tattooing.” In this incident, Josephine’s master cut over 100 marks into her body and proceeded to rub a mixture of salt and flour into the open wounds. This procedure marked Josephine as “property.”6 Needless to say, Josephine had many reasons to throw in the towel. The gruesome nature of these stories is important not to glorify violence but rather to highlight Josephine’s challenging circumstances. Despite these circumstances, Josephine did not throw in the towel. She did not allow things outside her control to constitute an obstacle to her sanctity. Rather, relying not on her strength but on Christ, Josephine utilized her freedom to rise above her circumstances and become a Saint.

Lesson 2: Identity

Toward the end of her life, Josephine’s religious community asked her to recount her life in a biography. An Italian woman, Ida Zanolini, interviewed her. Zanolini tells the tragic story of Josephine’s receiving her name. Bakhita was not Josephine’s given name but rather a name that she received from her Arab kidnapers. Zanolini records Josephine’s story as follows:

It was nightfall when we came out of the woods, but the two Arabs did not show signs of slowing down…” Black girl, what is your name?” asked the one who kept hold of her. … The little one … wanted to reply but could not. … “Answer!” ordered the slave driver rudely. … A few incoherent syllables spilled from her lips… “Call her Bakhita, and don’t waste your time with that little snot-nose,” said the other with a crack of his whip. … “Do you understand? From now on, your name is Bakhita. And don’t forget it.” What an ironic name! Bakhita means “lucky,” and in that moment, who could be more unlucky than she?7

To her death, Josephine had no recollection of her given name nor any memory of her birthdate. She lost any positive sense of self that she may have received from her parents when she was kidnapped. She learned a new language and lived in a new place, and all good memories of home were beaten out of her. The work of the slave traders in Josephine’s story is similar to the work of the devil in our own lives. Satan wants us to forget our true homeland, our true origin as a son or daughter of God. The only route back to our true identity is the saving love of Christ. Josephine knew this all too well. For this reason, Josephine regarded January 9, 1890—the day of her baptism—as more important than the day of her birth because it was on that day that Josephine received her true identity in Christ.

Lesson 3: Gratitude

As an old nun, Bakhita was asked what she would do if she were ever to meet her captors and torturers. She responded very quickly that she would kneel and kiss their hands because if it had not been for them, she said, she would not have been a Christian nor a religious sister.8 Few of us have stories as difficult as that of a slave, but we all have people we must forgive. The most basic of Christian prayers, the Our Father, includes a line many of us have uttered countless times: “Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” We are all sinners, and thus all require the radical forgiveness of Christ. Josephine Bakhita didn’t only forgive those who sinned against her; she viewed them with gratitude! I suspect Josephine did not have this gratitude as a young person after her kidnapping or “tattooing,” but she did reach a place of gratitude by the end of her life. That’s something for which all of us can strive. Imagine if we could approach others with the gratitude of Saint Josephine Bakhita!

Lesson 4: Discipleship

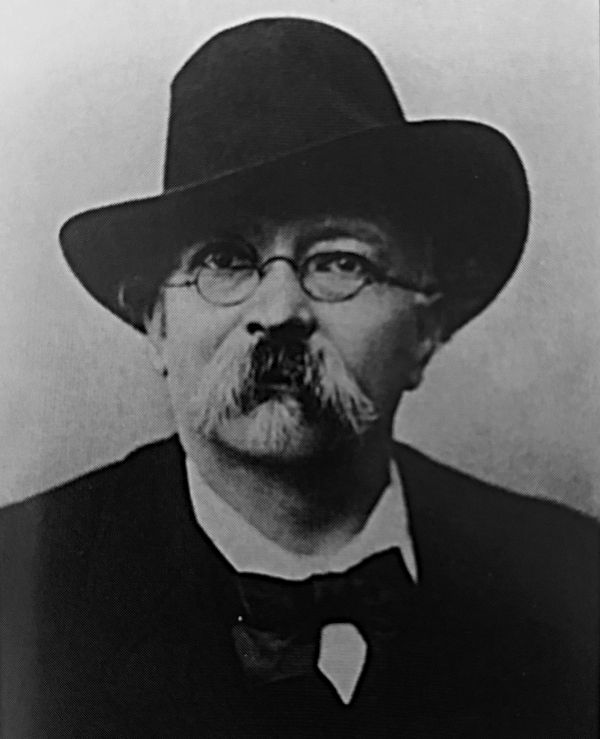

Bakhita worked in Venice as a nanny to her owner’s daughter. Living in a Salesian monastery, Josephine helped to raise the young girl. During that time, Bakhita met Illuminato Checchini, her owner’s estate manager. Checchini was not a priest or a religious brother. Nevertheless, as a layman, he became the first person to introduce young Bakhita to Christ. Bakhita recounts an early interaction with Checchini, in which he gave her a small crucifix:

As he gave me [a] crucifix he kissed it with devotion, then explained that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, had died for me. I did not know what a crucifix was, but I was moved by a mysterious power to keep it hidden, out of fear that the lady would take it away. I had never hidden anything before, because I had never been attached to anything. I remember that I looked at it in secret and felt something inside that I could not explain.9

Checchini presented the Gospel to Bakhita, but he didn’t only do that. In 1 Thessalonians 2:8, Saint Paul says to a group of new Christians, “So, being affectionately desirous of you, we were determined to share with you not only the Gospel of God, but our very selves as well.” In this passage, Paul describes how he chose to form new Christians in Thessalonica, and it was precisely this same manner that Checchini embodied when he evangelized the young Bakhita. One might say that Checchini didn’t merely evangelize Bakhita; Checchini discipled Bakhita. That is, he shared his very life with her. He took an interest in her faith formation. He showed her hospitality whenever the need arose. He introduced her to others who taught her to pray. All of this is to say that Checchini evangelized both with his words and also with his entire life!

Lesson 5: Simplicity

The last lesson from Saint Josephine Bakhita concerns her simplicity. If you are reading this post and received at least a middle school education, you are substantially better educated than Bakhita. You probably speak better English than Josephine spoke Italian, and there is a good chance you come from a more stable upbringing (that is, more than an enslaved person’s upbringing!). Considering all these factors together, you have received many things of which Josephine only dreamed! There is no reason you, too, cannot become a Saint! Let’s not make excuses, blaming our circumstances for our sin. Let’s not allow our toxic culture to form our identity; rather, let us root our identity in Christ! Let us live lives of profound gratitude! And finally, let us not keep all this to ourselves. Let us disciple our peers as Checchini discipled Bakhita. Thus, may we not come to heaven alone but with a crowd of friends at our side!

- Pope Saint John Paul II, Cappella Papale for the Canonization of 123 New Saints. October 1, 2000.

- Roberto Zanini, Bakhita: From Slave to Saint (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2013), 38.

- Melanie Rigney, Radical Saints: 21 Women for the 21st Century (Cincinnati, OH: Franciscan Media, 2020), 113-115

- Roberto Zanini, Bakhita: From Slave to Saint, 67-68.

- Roberto Zanini, Bakhita: From Slave to Saint, 56-57.

- Roberto Zanini, Bakhita: From Slave to Saint, 60.

- Zanolini interview as contained in Rigney, Bakhita: From Slave to Saint, 39.

- Melanie Rigney, Radical Saints: 21 Women for the 21st Century, 115.

- Roberto Zanini, Bakhita: From Slave to Saint, 79.