What is most important in the Christian life? If you were asked this question, how would you respond?

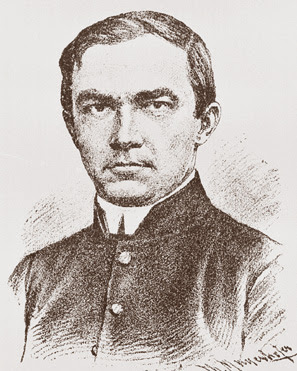

My purpose here is a simple one: to introduce you to the works of one such theologian, Matthias Joseph Scheeben (1835-88), and one of the leading ideas of his thought relevant to your life as a Christian.

Who is Matthias Scheeben?

Scheeben is probably the greatest Catholic dogmatic theologian of the last several centuries. Once well known, his reputation went into decline after the 1960s; however, he is presently making a comeback.

What is Scheeben’s thought all about? Why should anyone care about him today? In a nutshell, the answer is that he writes about what is most important in the Christian life. His thought is all about what theologians sometimes call human deification—the union or “marriage” of God and man.

This term “deification” as used in Christian contexts requires some explanation so that it is not abused. So why talk about it at all? The answer is that God talks about it in Scripture, so we have to talk about it in order to preach the Gospel. Theologies of human deification are really just the working out of an idea that lay at the foundation of the proclamation of the Gospel in the New Testament: God no longer dwells in a temple made of stone, like in the Old Testament. Instead, he now dwells in temples made of flesh, namely, in Christ and in us Christians when we come to share in the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Of Christ, Scripture says that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1:14, RSV, 2nd CE). Here, the “Word” or “Son of God” comes to dwell in a temple of flesh, which St. John elsewhere calls “the temple of his body” (Jn 2:21).

Of ordinary Christians, the members of Christ’s body, St. Paul tells us: “Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, which you have from God?” (1 Co 6:19). Likewise, St. Peter tells us quite simply that through Christ’s work we have “become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4).

When Scheeben takes up human deification in his writings, he is trying to give a reasoned account of this Scriptural indwelling of God or the Holy Spirit in our souls. It is the reality that stands behind what the New Testament calls “the grace of God.”

Still, a term like “deification” is open to a number of misunderstandings. So, let me start by explaining what Scheeben does not mean by this term. He does not mean that we simply become God and cease to be creatures. That is impossible. God cannot change. And we cannot cease to be creatures without ceasing to be at all.

What, then, does Scheeben mean? He means that God’s grace, when poured out into souls, allows us to “partake” of God. To explain this idea, he frequently uses a metaphor often found in the Church Fathers, namely: the image of a length of iron being plunged into fire.

In this image, the fire is God, and the iron—our humanity. The fire doesn’t change when the iron is plunged into it. What changes instead is the metal. It heats up. In the process, it begins to glow and becomes white-hot. Eventually, it will emit heat and light on account of the fire in which it is immersed. Note again that it is not the fire that has changed. Rather, the fire has lent its own qualities (heat, light) to the metal. Just so, God’s grace produces a change in us that makes us like him and allows us to reach out to him. This is what Scheeben is getting at with his language of deification.

Of course, heat and light in a length of metal are only images that point to spiritual effects in us. So how does God’s grace change us? Well, with respect to our souls, the metaphors of heat and light point to spiritual effects that God works in our inner depths.

In our intellects, this deification of the mind begins when God gives us the gift of faith, which is a kind of light. When a person has an experience of conversion, they have a kind of “aha moment” when they begin to see the Lord in a new light. This is the beginning of the deification of our mind.

In our wills, this deification takes place when God pours his love into our hearts (cf. Rom 5:5). Spiritual writers frequently depict this love as a “fire” on account of the burning sensation that love produces in our chest.

This share in God will also spread to our bodies in the resurrection. On that day, we will become immortal like God, when every trace of corruption and death is removed from our frame and we rise again to the glorious life of the age to come. As St. Paul puts it, “this perishable nature must put on the imperishable, and this mortal nature must put on immortality” (1 Co 15:53).

Scheeben’s works are all about this biblical idea of deification by God’s grace. His writings are about what it means for God to pour out this light and fire into our soul, something that is relevant to each one of us at all times, since he is writing about the union with God to which we are called in Christ.

What books by Matthias Scheeben should we read?

For anyone that would like to read Scheeben for themselves, I would recommend first his devotional work, The Glories of Divine Grace. This is an accessible work written for a lay audience. It is a profound meditation on the treasure of grace that God gives to souls.

After this, I would recommend the more advanced reader try and tackle his 800-page The Mysteries of Christianity. This is the masterpiece of his youth (he wrote it in his mid-twenties!), and it is written for an educated lay audience. It is all about the Trinitarian God transforming souls by the fire of his grace for the purpose of union with himself. This work can be challenging at times; still, it is an incredibly beautiful work.

I would also, of course, recommend his Handbook of Catholic Dogmatics, but with a caveat: it is a technically demanding work that asks a lot of its readers. His major 6-part work, the Handbook of Catholic Dogmatics, is currently being published in its entirety in English for the first time by Emmaus Academic in Steubenville, OH. It is set to appear in 8 volumes—of these, four are currently available, including his entire Christology and Mariology in Dogmatics, Book 5, Parts 1 and 2. It will press you to your limits and beyond. Reading it is, really, the intellectual equivalent of an Ironman Triathlon. But as St. John Paul II liked to say: “do not be afraid to set out into the deep!”