A startling 2015 study from Microsoft claimed that digital media consumption is causing our attention spans to shrink and that they had dropped to an alarming 8 seconds. 8 seconds?! Think about that. It’s (supposedly) shorter than the attention span of a goldfish. How insulting…and frankly horrific, if true.

The poll was widely criticized. Its methods disproven and its conclusions dismissed. But why was it so popular? Why were so many people talking about it? I think because even if the actual data wasn’t true, the poll conveyed something that many people perceive. It feels like our culture has a dwindling attention span.

Distraction

The truth is, our world is a distracted universe. We leap from app to app, scrolling mindlessly, looking for a photo or caption to catch our eye. As algorithms continue to improve – will Facebook ever catch up to TikTok? – we have become increasingly dependent on the content served to us by platforms we don’t control. They keep us engaged; they intentionally work to keep us from putting the phone down. How many times have our heads hit the pillow with flashes of light lingering from the content we were just viewing?

And why is it that these apps capture our attention? I don’t mean to investigate the technological methods they use—someone else can answer the mystery of the algorithm. I want to point out something deeper: What is it about us as human beings that makes us susceptible to the catchy videos and stunning photos?

Human beings are curious cats

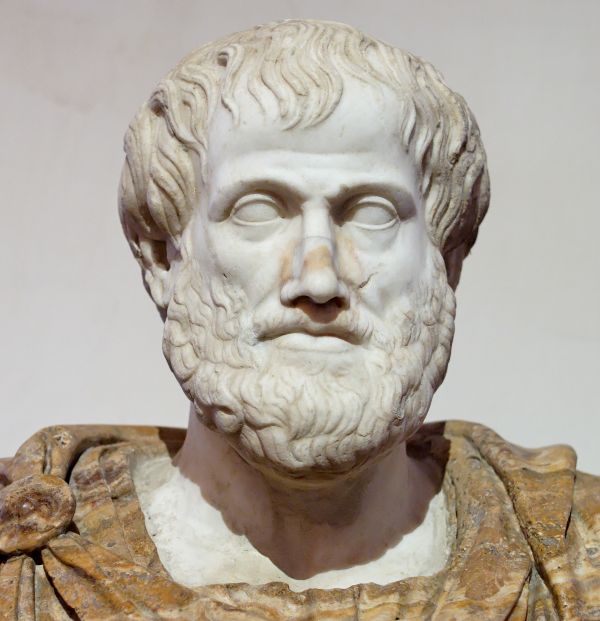

Two thousand years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle confidently declared, “All men desire by nature to know.” And you know what? I think Aristotle’s right. Human beings are thinking things. He claims that it belongs to us by our nature as rational beings, with intellect and will, to want to think, and by thinking come to actually know things about ourselves, others, and the world.

We human beings crave neighborhood gossip and celebrity news. We like to know how things work (consider the rise of tech news in the last decade) and the latest trends (imagine not understanding the latest meme…how embarrassing!). We want our friends to spill the tea and TikTok promises to keep us up to date with breaking news. These behaviors feed our deepest instincts. We are curious by nature. We want to know. We are, as the saying goes, “curious cats.”

Is curiosity good or bad?

In our culture, we generally understand curiosity to be virtuous. Parents and teachers encourage us from the time we’re little to ask questions and explore. Growing up, my mom and my Aunt Helen took me, my sisters, and my cousins on regular field trips. We explored zoos and science museums. We went to fairs and aquariums. They taught us to be inquisitive, to ask questions and seek understanding.

But for St. Thomas Aquinas, the Dominican Order’s great medieval theologian, curiositas (a Latin word which looks like our English word curiosity) is a vice rather than a virtue. In excess, it’s a bad thing rather than a good thing. And St. Thomas warns us that we must be very careful about it, because curiositas has a way of sneaking in and ruining our otherwise noble intentions. For this reason college students must be especially on guard against it!

When curiosity goes astray

St. Thomas points out that knowledge of the truth is, in and of itself, a good thing. However, knowledge can become a stumbling block – even sinful – when we pursue it out of pride or use our knowledge for sinful purposes. As St. Thomas says, “Vanity of understanding and darkness of mind are sinful.”

St. Thomas goes on to specify in his Summa Theologiae (ST II-II, q. 167, a. 1) four ways that our desire to know goes astray.

- First, we indulge in the vice of curiositas when we put off studying the things we have an obligation to study. Thomas describes this saying this vice occurs, “when a man is withdrawn by a less profitable study from a study that is an obligation incumbent on him.” He offers as an example taken from a letter of St. Jerome, that priests reading plays and singing love songs rather than studying the Gospels fall into this category. Students doing deep dives on YouTube, although learning, are hurting their studies if by doing so they neglect the required homework and reading for class.

- Second, we offend virtuous study when we seek knowledge from unlawful teachers. St. Thomas says this happens when people try to know the future by communicating with demons. We might broaden that category a bit to include other kinds of dangerous superstition, including tarot cards, horoscopes, and fortune tellers. I’d add to this category that we should be cautious about other online sources, especially websites that claim to be Catholic, but instead of building up the Church, they sow doubt, animosity, and discord. Practicing media literacy means checking sources and thinking critically about what we’re reading and sharing on social media. We must always be committed to pursuing the Truth rather than an ideology or a political program.

- Third, we hurt true study when we fail to refer things back to their ultimate goal. For St. Thomas, and for every Christian, the goal of our life is heaven. If we fail to keep that frame for our learning, we’ll be liable to dangerous error. St. Thomas quotes St. Augustine, saying, “In studying creatures, we must not be moved by empty and perishable curiosity; but we should ever mount towards immortal and abiding things.” If we forget the frame of our heavenly goal, we’re distorting everything that we were made for. This is the problem that haunts many political and sociological ideologies. As Christians, we must constantly assert that we were made for life with God in heaven. If we fail to do so, we will injure the truth of who we are.

- Finally, we fall into error regarding learning when we seek to know what is beyond us. We must practice a certain humility before the Truth. St. Thomas says that when we try to know more than we’re capable of, we risk falling into error. Fr. Antonin Sertillanges, O.P., says, “We must not overestimate ourselves, but we must judge of our capacity” (The Intellectual Life). Remember that Scripture tells us that humankind’s first sin was pride (cf. Sirach 10:15). The genuine search for knowledge requires docility. And in order to not get trapped or frustrated, we must move on or surrender when something is beyond our capacity to grasp, or even beyond our state in life.

Not just a modern problem

But despite the changes in technology we face, distraction isn’t just a modern problem. In the Middle Ages the monastic scribes who copied manuscripts were keenly aware of the temptation to let their minds wander. After all, they were preserving the Sacred Word. An error in copying a Biblical manuscript was not simply bad scholarship—it was an offense against God!

They were so concerned about distractions that they prayed against a demon that caused them to lose their places: Titivillus. He distracted the monks during their labors, trying to get them to misspell, omit words, and otherwise confuse the project of revelation.

Study well

So what are we to do? We must cultivate the virtue of studiositas; in plain English, the virtue of study. We must savor and love our search for truth, keeping in mind that Truth always leads us to God. As Saint Augustine says, “For where I found truth, there found I my God, who is the Truth itself, which from the time I learned it have I not forgotten.” Our study should help us to love more deeply, to delight in contemplation of all that God has made. And if we find ourselves becoming distracted, suffering from curiositas, we simply pause, take a deep breath, utter a simple prayer, and direct our mind back to our work.