The Cross (1 Peter 3:18, Romans 5:8)

Christians are very familiar with the cross. They have crosses in their churches. Crosses in their homes. Some wear crosses as jewelry around their neck. Others sing Christian songs about how powerful the cross is. Catholics regularly make the sign of the cross. The average Christian has heard the basic idea that “Jesus died on the cross for our sins.” But do they understand what it really means and what it’s all about? The Cross is at the very center of the Christian faith, and yet few Christians can adequately articulate this most foundational belief.

How about you? If you had to talk to someone else about how the cross works — how Jesus’ death on the cross solves the problem of humanity’s sin — how confident would you be in explaining it?

One popular Christian interpretation of the cross stresses that Jesus is the innocent victim taking on our punishment. Because we are sinners, we deserve God’s punishment and death. God is a God of justice, and we will be forever separated from him unless sin is dealt with. But God is also a God of mercy. So, God sent his only Son to die for our sins. Jesus volunteers to step in and receive the punishment we deserved. He lovingly takes on the full brunt of God’s wrath so we don’t have to. That’s how much God loves us! He sent his Son, Jesus Christ, to endure the punishment that we deserved so that we can enter the kingdom of heaven!

But let’s think about that for a moment. Does that explanation of the cross make sense? Imagine two sons in a family: one has done something seriously wrong, and the other is innocent. What would you think of a father who is getting ready to pour out his wrath and punish his guilty son, but instead, at the last minute, lets it all out on the innocent one? What if the innocent son volunteered to take on the wrath of the father so that the guilty son didn’t have to? In this scenario, the father doesn’t care who receives the punishment, as long as punishment is given.

How does that possibly solve the problem? A father who punishes the innocent instead of the guilty is neither a father of justice nor of mercy. He’s just randomly meting out punishment; and as long as the punishment gets delivered, he is somehow satisfied. Is this the correct view of God?

This is certainly not the Catholic view of the Cross. At the center of the Catholic understanding of the Cross is not divine wrath and punishment, but love. Pope St. John Paul II once explained that what gives the cross its redemptive value is “not the material fact that an innocent person has suffered the chastisement deserved by the guilty and that justice has thus been in some way satisfied.” Rather, the saving power of the cross “comes from the fact that the innocent Jesus, out of pure love, entered into solidarity with the guilty and transformed their situation from within.”[1] It’s not the fact that punishment has been unleashed on an innocent person and that God’s anger has somehow been appeased. Rather, it’s Christ’s unique and total gift of himself in love that gives the Cross its redemptive value. As the Catechism explains, “It is love ‘to the end’ (John 13:1) that confers on Christ’s sacrifice its value as redemption and reparation, as atonement and satisfaction” (CCC 616, see 1 Peter 3:18 and Romans 5:8).

In this chapter, we will take a deeper look at this central mystery of the Christian faith: Christ’s death on the cross.

The Bridge (Romans 3:23, 6:23)

The medieval mystic St. Catherine of Siena described Jesus Christ as the bridge between us and God. Using this image, let’s consider how Jesus’ death on the cross bridges the gap between sinful humanity and the all-holy, all-loving God.

First, sin radically ruptures our relationship with God. We must feel the weight of how devastating the consequences of sin are. As Curtis Martin explains,

You are not who you were meant to be. Sin wounded you and separated you from God. Our problem is actually far worse than we might have imagined. At first glance, we may think that, with some effort toward self-improvement, we could close the gap between who we are and who we ought to be. It is simply not the case.

When we fell: The fall was universal — “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” (Rom 3:23).

The fall was severe — “For the wages of sin is death” (Rom 6:23).

The fall created a chasm so great that no human could bridge it even with the best of efforts. Through Saint Catherine of Siena, we are reminded that “…the road was broken by the sin and disobedience of Adam in such a way that no one could arrive at Eternal Life.” (The Dialogue of St. Catherine of Siena)[2]

Second, there is nothing we can do on our own to solve the problem of sin. Sin causes an infinite gap between us and God and we are finite human beings — there is no finite act of love, sacrifice or sorrow that we can perform to overcome this infinite gap.[3] As the Catechism explains, “No man, not even the holiest, was ever able to take on himself the sins of all men and offer himself as a sacrifice for all” (CCC 614).

Think of what happens in other relationships we have. When we hurt someone, we have a sense that we should do something — offer a gift of love, a sacrifice, an expression of our sorrow and desire to set things right — in order to bridge the gap of the relationship. The same is true in our relationship with God. But with God, the gift of love, the bridge, must be so much greater, infinitely greater. As Edward Sri explains,

In a marriage, for example, if a husband has hurt his wife, and he wants to repair the relationship, he will do something to make amends, to bring about reconciliation, to make up for his lack of love. He, of course, will say, “I’m sorry.” But he senses he should do something more. He might give her an embrace, buy her flowers, or take her out to dinner… some meaningful act of love that overshadows the lack of love he showed her. And the magnitude of that gift of love will correspond to the seriousness of the hurt he has inflicted on the relationship.

The same is true in our relationship with God. Our sin entails withholding our love for the God who so completely loves us. We, therefore, should offer God a gift of love that corresponds to the infinite gravity of sin committed against him. But no human being can do that. Not even the most saintly person could offer a gift of love that would atone for the sins of all humanity. Only a divine person could do that.[4]

And this leads to the third point: the God-man solution. As God and man, only Jesus Christ can bridge the infinite gap between us and God. As fully human, Jesus can represent us. He can offer an act of love on behalf of the entire human family. But because he is also fully divine, his act of love far surpasses anything a mere human could ever offer. Because of who Jesus is, fully human and fully divine, his total, self-giving love on the cross takes on infinite value. It is an infinite gift of love, offered on our behalf, that restores us to right relationship with the Father. Jesus is the bridge between sinful humanity and the all-holy God.

The Catholic Gospel: Transformation & Divine Sonship (2 Corinthians 3:18, 1 John 3:1-2, 2 Peter 1:4)

Now we have a better sense of the Cross. But Jesus came to do a lot more than die on the cross for our sins. If all Jesus did was die on the cross, humanity would have made amends with God. Things would be repaired and a right relationship with the Father would be restored. But God loves us so much that he wants so much more than merely a repaired, just, peaceful coexisting relationship with us. He wants our hearts. He wants to be fully united with us and share his blessed life with us forever. In fact, if all Jesus did was die on the cross for our sins, we wouldn’t have eternal life with him in heaven.

Here’s the key: Jesus didn’t come simply to die for our sins. He rose from the dead to give us new life. And he sent his Spirit into our hearts so that we could be transformed in Him and become God’s sons and daughters, sharing in his very divine life and love forever.

Curtis Martin explains an image that the Church Fathers gave us for the profound transformation in Christ that God wants to work in our lives:

Imagine a cold steel bar and a hot burning fire. They have almost nothing in common. If you place the cold rod in the hot fire, though, something amazing begins to happen: the rod begins to take on the properties of the fire. It grows warm, it begins to glow — and if you were to take the rod out of the fire and touch it to some straw, it could actually start a fire itself. Now image that the fire is God and we are the steel rod. When we are living in Christ… we begin to take on the properties of God.”[5]

This is so much more than merely being forgiven of our sins! Indeed, as Christ fills us with his life, we begin to think like Christ, serve like Christ, sacrifice like Christ. We take on the qualities of Christ: we become more patient, honest, generous, pure, and courageous like Christ. As St. Paul explains, we are being changed into Christ’s likeness from one degree of glory to another (2 Corinthians 3:18). Jesus doesn’t just want to pardon us like a judge. He wants to heal us like a physician. He doesn’t just want to forgive us; he wants to transform us. He doesn’t just want to save us from sin. He wants to save us for something — he wants to save us for sonship.

And this brings us to one of the most beautiful and crucial aspects of the Catholic Faith: how profoundly real our divine sonship is. When the Bible describes how God is our Father, we are God’s children, and we are all brothers and sisters in Christ, these are not pious metaphors. Through baptism, we really share in Christ’s divine life — the life of the Eternal Son of God, Jesus Christ, dwells within us. And that life of Christ within us is like the hot fire of his love changing the metal rod of our fallen human nature. Indeed, St. Peter explicitly states that we become “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4) — we begin taking on the character of Christ. The very divine life of the Son of God fills us and makes us God’s children. We become “sons in the Son.” St. John speaks in awe over this amazing gift: “See what love the Father has given us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are…Beloved, we are God’s children now” (1 John 3:1-2).

Note how St. John doesn’t say we are merely called God’s children. We are called children of God because that is what we really become! Because Christ’s Spirit, the divine life of the Son of God himself dwells in our hearts, we are truly sons and daughters, and we can truly call God Father!

Finally, consider how the profound reality of this gift is expressed whenever we pray the Lord’s Prayer. We say, “Our Father…” Two important points are made with these two opening words of the Lord’s Prayer. First, consider the word “Father:” We call God Father because he truly has become Father. As St. Paul explains, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Galatians 4:6). Second, consider the word “Our:” God is not merely my Father or your Father…he is truly Our Father because we are truly brothers and sisters in Christ, sons and daughters of the same heavenly Father. This is not a Christian figure of speech. The supernatural bond we share in Jesus Christ makes us truly brothers and sisters in Christ. Indeed, Christians share a brother and sisterhood that is more profound than the natural bonds we might share with siblings back home, for these are bonds that last forever. We are all part of one covenant family of God.

Thus, we can see that, when God sent his Son Jesus to die on the cross, he didn’t do so merely to save us from sin. He sent his Son because he wants to fill us with his divine life and adopt us as His children. And he doesn’t just want to forgive us. He wants to transform us—to heal our wounded human nature, perfect it and elevate it to share in his total, infinite, supernatural love, so that we take on the character of Christ. He doesn’t want to restore us to Eden, a mere earthly paradise; he wants to invite us to the everlasting perfect paradise of heaven. Moreover, he didn’t die to save us each individually, isolated from each other. He died to save us all together so that we can live as his children, sharing in his blessed life as true brothers and sisters in the one covenant family of God. This calling is far more than any invitation to get along and tolerate each other. This is an invitation to live in what Christians call “the beatific vision,” the very life of God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. All this is part of the amazing gift Jesus offers us through his death and resurrection: “God shows his love for us in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8).

More Background: Key Concepts

Atonement (CCC 616):

It is love “to the end” that confers on Christ’s sacrifice its value as redemption and reparation, as atonement and satisfaction. He knew and loved us all when he offered his life. Now “the love of Christ controls us, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died.” No man, not even the holiest, was ever able to take on himself the sins of all men and offer himself as a sacrifice for all. The existence in Christ of the divine person of the Son, who at once surpasses and embraces all human persons, and constitutes himself as the Head of all mankind, makes possible his redemptive sacrifice for all.

Sonship/Partakers of the Divine Nature (CCC 2009, 460):

Filial adoption, in making us partakers by grace in the divine nature, can bestow true merit on us as a result of God’s gratuitous justice. This is our right by grace, the full right of love, making us “co-heirs” with Christ and worthy of obtaining “the promised inheritance of eternal life.” The merits of our good works are gifts of the divine goodness. “Grace has gone before us; now we are given what is due. . . . Our merits are God’s gifts.” The Word became flesh to make us “partakers of the divine nature”: “For this is why the Word became man, and the Son of God became the Son of man: so that man, by entering into communion with the Word and thus receiving divine sonship, might become a son of God.” “For the Son of God became man so that we might become God.” “The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods.”

Sanctifying Grace (CCC 2000):

Sanctifying grace is an habitual gift, a stable and supernatural disposition that perfects the soul itself to enable it to live with God, to act by his love. Habitual grace, the permanent disposition to live and act in keeping with God’s call, is distinguished from actual graces which refer to God’s interventions, whether at the beginning of conversion or in the course of the work of sanctification.

Discussion Guide

Passages: 1 Peter 3:18; Romans 3:23, 5:8, 6:23, 2 Corinthians 3:18, 1 John 3:1-2, 2 Peter 1:4

Introduction

1. Launching Question: The cross is a very common symbol in Christianity: Christians have crosses in their churches, in their homes. Some wear crosses as jewelry around their neck. Others sing Christian songs about how powerful the cross is. Catholics regularly make the sign of the cross. What does the cross mean to you? What does it make you think of?

Allow the group to discuss.

The Cross (1 Peter 3:18, Romans 5:8)

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

Many of us know that Jesus’ death on the cross is a foundational aspect of the Christian faith. But how confident would you be explaining to others what the cross really is all about? How confident would you be explaining how the death of an innocent man solves the problem of our sin? Does the death of the Son of God on the Cross really make sense?

(Read 1 Peter 3:18)

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

A common interpretation of this passage and others like it, goes something like this:

God is a God of justice. Because we are sinners, we deserve God’s punishment and death. Unless sin is dealt with, we will be forever separated from him. But God is also a God of mercy, so God sent his only Son to die for our sins. Jesus volunteers to step in and receive the horrific punishment we deserved. He takes on the full brunt of God’s wrath so we don’t have to. That’s how much God loves us!

2. What do you think of this popular explanation of the Cross in some Christian circles? Does this make sense? Is it helpful? … Does anything sound off to you? Is there anything missing from this explanation?

Answer: Allow the group to discuss. Consider letting the group discuss the first two questions for a bit before introducing the second two questions. Help your group raise questions about whether or not this interpretation portrays God as a good Father.

3. Let’s look a little closer at that interpretation. Imagine two sons in a family: one has done something seriously wrong and the other is innocent. What would you think of a father who is getting ready to pour out his wrath and punish his guilty son, but instead, at the last minute, lets it all out on the innocent one? What kind of father would this be?

Answer: A father who punishes the innocent to spare the guilty is neither a God of justice nor a God of mercy. This would not be a good or loving father, but a cruel tyrant, who doesn’t care who receives the punishment just as long as punishment is given.

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

This is not the Catholic view of the Cross. Rather than a view of simply punishment and justice, the Catholic view of the Cross is all about love. Pope St. John Paul II once explained that the saving power of the Cross “comes from the fact that the innocent Jesus, out of pure love, entered into solidarity with the guilty and transformed their situation from within.” As the Catechism explains, “It is love ‘to the end’ (John 13:1) that confers on Christ’s sacrifice its value as redemption and reparation, as atonement and satisfaction (CCC 616).[6]

(Read Romans 5:8)

4. This passage states that Christ’s death on the cross is an act of love. As we discuss the cross today, why is it important to begin with the understanding that the cross is primarily as an act of love, and not merely a meting out of divine punishment?

Allow the group to discuss. Emphasize that if we don’t view the cross as an act of love, we end up with a distorted view of God, a God who simply needs to exact the proper amount of punishment, rather than a loving Father.

The Bridge (Romans 3:23, 6:23)

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

To understand the deeper meaning of the cross, we are going to use Scripture and an image from one of the great saints of the Catholic Church, St. Catherine of Siena. St. Catherine of Siena described Jesus Christ as the bridge between us and God. Using this image, let’s consider how Jesus’ death on the cross bridges the gap between sinful humanity and the all-holy, all-loving God. To understand this image, we will consider three basic points about the cross, based on the writings of great Catholic thinkers such as St. Catherine of Siena, St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Anselm:

1. The Chasm: Sin radically ruptures our relationship with God, causing a great chasm, an infinite gap, between us and God.

2. The Dilemma: There is nothing we can do to bridge that gap.

3. “The Bridge:” (The God-Man Solution): Only someone who is both God and man can restore us to the Father.

Let’s now take a look at these three basic points.

I. The Chasm

First, we must feel the weight of just how devastating sin really is. Let’s take a look at a couple passages from Scripture. (Note to leader: Have two members of your group look up one of these verses and read it aloud.)

(Read Romans 3:23)

(Read Romans 6:23)

5. What do these passages tell us about sin?

Answer: Sin was universal; we have all sinned (Romans 3:23). The consequences of the fall were devastating and lead to death (Romans 6:23).

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

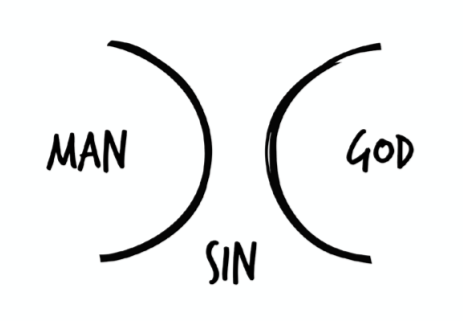

The fall was universal, and it was devastating. In fact, “our problem is actually far worse than we might have imagined. At first glance, we may think that, with some effort toward self-improvement, we could close the gap between who we are and who we ought to be. It is simply not the case.”[7] We would be eternally separated from God and living forever in death if the problem of sin was not dealt with. This is why St. Catherine was presented with an image of a great chasm separating God and man. (Note to Leader: on a sheet of paper, draw the first part of the Bridge Diagram: man on one side and God on the other, separated by sin.)

6. How have you experienced sin in your life? Have you tried to overcome a fault of your own and failed? What was that experience like?

Allow the group to discuss.

II. The Dilemma: Nothing We Can Do to Bridge the Chasm

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

Second, there is nothing we can do to repair our relationship with God. There is nothing we can do to bridge the chasm between us and God. There is no infinite gift of love we finite human beings can offer God to make up for our lack of love and bridge the chasm. It’s great for us to try to amend our relationships when we hurt others, but we run into a problem when we try to do this in our relationship with God. As Edward Sri explains:

Our sin entails withholding our love for the God who so completely loves us. We, therefore, should offer God a gift of love that corresponds to the infinite gravity of sin committed against him. But no human being can do that. Not even the most saintly person could offer a gift of love that would atone for the sins of all humanity. Only a divine person could do that.[8]

7. Now take a moment and think about other relationships in your life. When you hurt someone you love, what are some things you do to try to repair the relationship? How have you experienced something like this in your relationship with God? Have you ever felt the need to “get right with God?”?

Allow the group to discuss. Emphasize that when we hurt someone, we have a sense that we should do something — say “sorry,” offer a gift of love, a sacrifice, an expression of our sorrow and desire to set things right — in order to make amends, to bridge the gap in the relationship.

III. “The Bridge:” The God-Man Solution

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

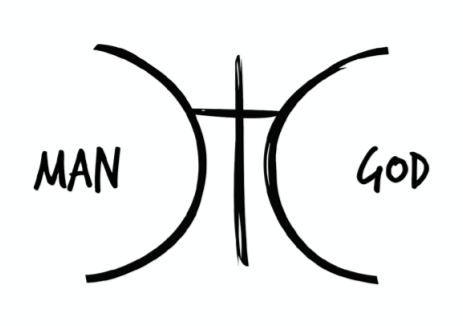

Third, this leads us to the God-man solution. As God and man, only Jesus Christ can bridge the infinite gap between us and God.

- As fully human, Jesus can represent us. He can offer an act of love on behalf of the entire human family.

- But because he is also fully divine, Jesus’ act of love far surpasses anything a mere human could ever offer. Because of who Jesus is, fully human and fully divine, his total, self-giving love on the cross takes on infinite value.

As the God-man, Jesus offers on our behalf an infinite gift of love that restores us to right relationship with the Father. Jesus is the bridge between sinful humanity and the all-holy God.

Note to Leader: on a sheet of paper, draw the second part of the bridge diagram: Jesus Christ and his cross as a bridge that crosses the chasm between us and God.  8. How might this Catholic understanding of the Cross be different from other explanations you have heard? Why is it important to have this understanding of the cross?

8. How might this Catholic understanding of the Cross be different from other explanations you have heard? Why is it important to have this understanding of the cross?

Allow the group to discuss.

The Catholic Gospel: Transformation & Divine Sonship (2 Corinthians 3:18, 1 John 3:1-2, 2 Peter 1:4)

We now have a better sense of the Cross. But Jesus came to do a lot more than die on the cross for our sins. If all Jesus did was die on the cross, humanity would have made amends with God. Things would be repaired and a right relationship with the Father would be restored. But God loves us so much, he wants so much more than merely a repaired, just, peaceful coexisting relationship with us. Let’s read more of what Scripture tells us.

(Read 2 Corinthians 3:18)

9. How does this passage give us a deeper understanding of what God is offering us in Christ?

Answer: Christ doesn’t only want to save us from sin; he wants to transform us, make us like him, and change us “into his likeness”.

Curtis Martin explains how the early Church spoke about this transformation:

Imagine a cold steel bar and a hot burning fire. They have almost nothing in common. If you place the cold rod in the hot fire, though, something amazing begins to happen: The rod begins to take on the properties of the fire. It grows warm, it begins to glow—and if you were to take the rod out of the fire and touch it to some straw, it could actually start a fire itself. Now image that the fire is God and we are the steel rod. When we are living in Christ…we begin to take on the properties of God.”[9]

10. What does it mean that we can “begin to take on the properties of God?”

Answer: As Christ fills us with his life, we begin to think like Christ, serve like Christ, sacrifice like Christ. We take on the qualities of Christ: we become more patient, honest, generous, pure, and courageous like Christ. We can begin to say with St. Paul, “It is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 2:20).

Note to the leader: Please read aloud.

This transformation in Christ is truly amazing! But, there’s still even more to what Christ offers us. Let’s read a couple more passages. (Note to leader: Have two members of your group each look up a passage and read it aloud.)

(Read 1 John 3:1-2)

(Read 2 Peter 1:4)

11. What do these passages tell us about what Christ offers?

Answer: For 1 John 3:1-2: Note how St. John doesn’t say we are merely called God’s children. We are called children of God because that is what we really become! Because Christ’s Spirit, the divine life of the Son of God himself dwells in our hearts, we are truly sons and daughters, and we can truly call God Father! In fact, when the Bible describes how God is our Father, we are God’s children, and we are all brothers and sisters in Christ, these are not pious metaphors. Through baptism, we really share in Christ’s divine life—the life of the Eternal Son of God, Jesus Christ, dwells within us.

For 2 Peter 1:4: St. Peter explicitly states that we become “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4) — we begin taking on the character of Christ. The very divine life of the Son of God fills us and makes us God’s children. We become “sons in the Son.” And that life of Christ within us is like the hot fire of his love changing the metal rod of our fallen human nature.

Note to the leader: Please read aloud. From these passages, we can see that, when God sent his Son Jesus to die on the cross, he didn’t do so merely to save us from sin. He sent his Son because he wants to fill us with his divine life and adopt us as his children. And he doesn’t just want to forgive us. He wants to transform us — to heal our wounded human nature, perfect it and elevate it to share in his total, infinite, supernatural love, so that we take on the character of Christ (Philippians 3:21, Romans 12). He doesn’t want to restore us to Eden, a mere earthly paradise, he wants to invite us to the everlasting perfect paradise of heaven. Moreover, he didn’t die to save us each individually, isolated from each other. He died to save us all together so that we can live as his children, sharing in his blessed life as true brothers and sisters in the one covenant family of God.

12. After discussing Christ’s death on the cross and all that he offers, what stands out to you the most? And what does all of this mean for you personally?

Allow the group to discuss.

[1] John Paul II, General Audience, Wednesday, 26 October 1988.

[2] Curtis Martin, Making Missionary Disciples (N.p.: Fellowship of Catholic University Students, 2018), 46-47.

[3] The great medieval theologian St. Anselm explained that God’s glory and honor are infinite. To sin against his infinite honor incurs an infinite debt. We, however, are finite creatures, incapable of offering an infinite act of love to overcome that infinite gap. Moreover, Anselm also points out that we already owe God our entire lives. What could we possibly give to God that we don’t owe him already? See Anselm of Canterbury, Cur Deus Homo.

[4] Edward Sri, Love Unveiled: The Catholic Faith Explained (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2015), 91.

[5] Curtis Martin, Making Missionary Disciples, 13.

[6] See Edward Sri, Love Unveiled: The Catholic Faith Explained, p. 89.

[7] Martin, Making Missionary Disciples, 46-47.

[8] Sri, Love Unveiled, 91.

[9] Martin, Making Missionary Disciples, 13.