It’s difficult to imagine the sense of despair—and also hope—many Jews must have experienced in the first century. For most of the last 500 years, God’s people had been without a Davidic king, oppressed by various foreign powers and suffering like exiles in their own land. The Roman Empire represented the latest and fiercest of the regimes oppressing the Jewish people. Persecuted by the unprecedented force of Roman violence, taxation, and idolatry, the Jewish people were, on many levels, suffering as never before.

Nevertheless, against this backdrop of pain and misery, their expectation and desire for a restored kingdom and a messianic savior were reaching a fevered pitch.

It is in the midst of this drama that a strange figure appears in the desert, clothed only in animal skins and eating insects and wild honey. His name is John, and he stands at the Jordan River, telling the people, “Repent!” Just as Joshua led the people through the wilderness to this very river and into the Promised Land centuries ago at the culmination of the first exodus, so now John leads the people to these same waters and invites them to a new and even greater exodus: an interior journey away from sin. He proclaims, “Repent…for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.”

The Old Testament prophets foretold that God would one day come to rescue His people from their oppressors and restore the great Davidic kingdom. They also depicted that restoration of Israel as a new exodus. It’s no wonder, then, that John’s message in the desert by the Jordan River (recalling the climax of the Exodus story) and his announcement about a great kingdom dawning (stirring the hopes about a future Davidic king) drew a lot of attention. Large crowds went out to follow him, hoping that the long-expected kingdom would soon arrive.

Then, one day, it finally happens: A young and unknown descendant of David named Jesus comes out to join this movement in the wilderness. He goes to John and asks to be baptized. As He rises from the waters, the Spirit of God descends upon Him, and a heavenly voice speaks the words that signal His true identity: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (Mt 3:17). Indeed, now that Jesus is present, the kingdom of heaven is truly at hand.

The King

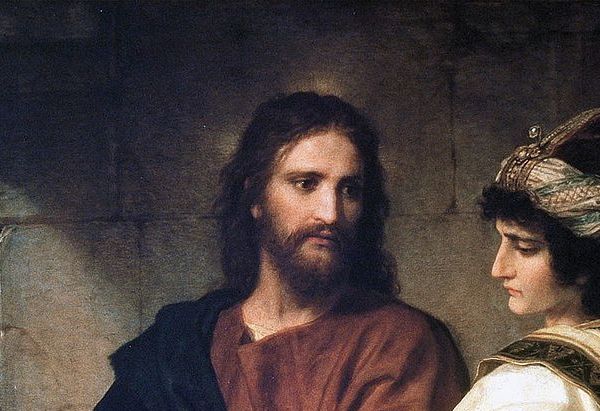

At the heart of Jesus’ public ministry, we find more than abstract principles about ethics or salvation. As king, Jesus’ mission is to restore the kingdom of David. Everywhere He goes, He preaches “the gospel of the kingdom” (Mt 4:23), which attracts people from all around the land (Mt 4:25). His famous Sermon on the Mount begins and ends with a message about the kingdom. Through His powerful healings, He is recognized as “the son of David,” the true king of the Jews. Much of His preaching and many of His parables elaborate upon this kingdom with various images: It is like a field, a treasure, a mustard seed, a pearl of great price. Clearly, Jesus is claiming to usher in a great kingdom. In the first-century Jewish context, practically everyone would understand that kingdom to be the promised restoration of the kingdom of David.

At a key turning point in His public ministry, Jesus calls His disciples to recognize that the central issue of this kingdom is His very identity. He asks the disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” In response, Peter declares, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Mt 16:16). The term “Christ” refers to the anointed messiah king whom the prophets foretold.

Peter is the first to refer explicitly to Jesus as the Christ, the messiah. In response to Peter’s faith, Jesus gives Him the keys of His kingdom:

“And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church and the powers of death shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” (Mt 16:18-19)

These keys of the kingdom symbolically represent one of the most important offices in the Davidic kingdom, the head of the royal household. In the Davidic dynasty of old, the king had a prime minister–like official who was vested with the king’s authority and who governed the day-to-day affairs of the kingdom. His office was symbolized by “the key of the house of David” (Is 22:22). With this background in mind, it becomes clear that, when Jesus the king gives Peter the keys of the kingdom, he is establishing him as the prime minister in the kingdom that He is establishing. It is no surprise that the Catholic Church sees this passage as shedding light on the papacy since it highlights the important leadership role Jesus gave to Peter (and those who succeed him in this office of prime minister) over the Church Christ founded.

Climax of the Covenant

Jesus’ kingdom will be established in a paradoxical manner. Despite His many Jewish followers, the rulers of the Jews reject Him, handing Him over to the Romans to be crucified. Yet it is through His death on that cross and His resurrection on the third day that Jesus saves His people and establishes the neverending kingdom.

How does this occur? Consider how all the covenants we have been studying—from Adam, Noah, and Abraham to Moses and David—converge on the cross and find their fulfillment there, shedding light on the meaning of Christ’s atoning sacrifice.

Jesus, as the new Adam, finds Himself in a garden (the Garden of Gethsemane) tested by the devil, but He proves to be a faithful Son (whereas Adam was unfaithful). He bore Adam’s curses—sweat, thorns, and death (Gn 3:18-19)—by sweating blood, being crowned with thorns, and dying on the cross (see Chapter One).

Like Noah, Jesus is a faithful son of Adam in the midst of a corrupt world. Like Noah, He offers salvation to His household, the family of God. Noah’s salvation came through the ark, which the Church Fathers saw as prefiguring the Church. Just as God used the ark to save Noah’s family from the flood, so does Christ save all humanity from sin through the Church He established by His death and resurrection (see Chapter Two and Catechism, no. 845).

Like Abraham’s only beloved son Isaac, Jesus, as the heavenly Father’s only beloved son, travels on a donkey to the ancient Mount Moriah, now in the city of Jerusalem, and bears the wood of sacrifice to Calvary in order to offer himself as a voluntary victim to atone for our sins and bring blessing to the entire world. (see Chapter Four).

Like Moses, who began the exodus from Egypt with the Passover, Jesus begins His passion—the work of the new exodus—with the Passover meal at the Last Supper. Just as the first Passover lambs were slain to spare the first-born Israelites in Egypt, so Jesus is sacrificed on the cross as the new Passover lamb, offering redemption to all humanity. And as the Passover was not just a sacrifice but a meal, all who participate in this new Passover are called to consume the flesh of the sacrificial lamb, Jesus Christ, in the Eucharist (see Chapter Six and Jn 6, 1 Cor 5:6-7).

And most of all, in a paradoxical way, Jesus’ passion and death reveal His royal status as the true Davidic king (see Chapter Eight). He is crowned, but with thorns; He is vested with a royal robe, but in mockery; He is hailed as a king by the soldiers, but in jest. His royal elevation is not to a throne, but to a cross with a simple sign above His head that reads, “Jesus the Nazorean, King of the Jews.” Though the Romans intended all this to mock Jesus’ royal claims, the Gospel writers highlight how they unwittingly reveal the truth: Jesus is, in fact, the true King of Kings. While His crucifixion is seen by the world to be His moment of defeat, it is actually His moment of triumph over sin and death. His execution is actually His enthronement as He establishes His kingdom, the Church.

Not Just the Jews

Jesus clearly fulfills all the covenants God made to His people. However, God’s people are not just the Jews; like David himself, the messianic son of David is to reign over all of Israel, which originally consisted of all twelve tribes. As we saw in the previous chapter, the Jews, as the name suggests, are those Israelites who remained loyal to the divinely established Davidic dynasty in the southern kingdom of Judah. The ten northern tribes rebelled against their king and established their own kingdom, only to be invaded by the Assyrians in 722 B.C.—which became known as Samaria.

The Assyrians had a particular way of treating their vanquished foes. Most of the defeated Israelites were scattered into foreign territories, but a small portion of them were left behind in the land. The Assyrians then brought in pagans from five other nations that they had conquered (2 Kgs 17:24-31). The result was that the northern tribes remaining in the land found themselves dwelling side by side pagan peoples and their idolatrous practices. They eventually intermarried with these peoples, yoking themselves to their pagan way of life and even their foreign gods. It was thus that the ten northern tribes lost their ethnic and religious identity.

In Jesus’ time, this mixed population of descendants from the old Northern Kingdom was known collectively as the Samaritans. They were hated by their estranged brethren, the Jews, for their unfaithfulness to Yahweh throughout the centuries and for their intermarriage with godless people. In fact, God sent the prophets to the northern kingdom and warned them that their idolatry was an act of covenant infidelity, likening it to adultery. This was a most fitting description, since Yahweh’s covenant relationship with Israel was likened to the kind of intimate union that exists between a husband and wife: Yahweh was the bridegroom and Israel was His bride. The Samaritans’ unfaithfulness to the covenant and their worshiping of other gods was, according to the prophets, similar to the infidelity of a spouse.

One of those prophets who confronted Samaria was a man named Hosea. At the same time that Hosea spoke out against Samaria’s sins, his own life embodied the broken relationship between God and His people. At the start of his prophetic ministry, Hosea was called to marry a prostitute, who went on to commit flagrant adultery and conceive children by other men. The public infidelity of Hosea’s wife served as a powerful image to illustrate Israel’s own unfaithfulness. Like Hosea’s wife, Israel was an unfaithful spouse whose idolatry was devastating for her relationship with Yahweh.

Yet even in the face of Israel’s spiritual harlotry, Hosea tells the people that there will be a time when Yahweh, the divine husband, will come to his spouse again, speak to her in love, and call her back into relationship.

“Therefore, behold, I will allure her, and bring her into the wilderness and speak tenderly to her…. For I will remove the names of the Ba’ls from her mouth, and they shall be mentioned by name no more. And I will make for you a covenant…. And I will betroth you to me forever; I will betroth you to me in righteousness and in justice, in steadfast love, and in mercy. I will betroth you to me in faithfulness; and you shall know the Lord.” (Hos 2:14, 17-18, 19-20)

This prophecy was given just before the northern kingdom was conquered by the Assyrians. To give this destitute Samaritan people hope, God reminds them that He will never abandon His bride. He foretells that, despite her infidelities, He will speak kindly to her and eventually woo her back into the fullness of His covenant love.

All’s Well that Ends Well—John 4

This background provides important context for understanding Jesus’ public ministry in the Gospel of John. After gathering Jewish disciples in Galilee (Jn 1) and teaching and performing miracles for the Jews in Jerusalem (Jn 2), Jesus takes His disciples into the land of Judea where they begin to baptize the Jews (Jn 3). John the Baptist sees the call to Christ’s baptism as a spousal gesture, referring to Jesus as the bridegroom coming for His chosen people (Jn 3:29-30).

But Jesus’ bride is not just the Jews, and the chosen people extend beyond the borders of Judea. Thus, Jesus next leaves Judea and goes to Samaria, the land where many people from the separated ten northern tribes dwell.

As He enters this region, Jesus goes to a well where a woman comes to draw water—an evocative setting in light of the Old Testament. Many of Israel’s ancient leaders found their wives at a well: Isaac’s wife Rebecca (Gn 24:11), Jacob’s wife Rachel (Gn 29:2), and Moses’s wife Zipporah (Ex 2:15). Now, Jesus, who already has been described as the “bridegroom” in John’s Gospel, meets a Samaritan woman at a well.

He asks her for a drink, which shocks her. She says, “How is it that you, a Jew, ask a drink of me, a woman of Samaria?” (Jn 4:9). Her surprise reflects the tragic history of her people, who had been at odds with their Jewish kinsmen for nearly a thousand years. Coming as the new, royal son of David, Jesus breaks down these barriers and speaks kindly to this Samaritan woman.

As we listen to their conversation, we discover that the Samaritan woman has had a heart-wrenching life—and one that actually embodies the disastrous history of her nation. She has suffered through the misery of marital infidelity. Like Samaria, she had been an adulterous wife; she had yoked herself to five different men, just as Samaria had yoked itself to five foreign nations and their idolatrous practices (2 Kgs 17:29-34). Her life, therefore, is an icon of the covenant infidelity of Israel that Hosea had condemned.

But now, Jesus tenderly approaches her as the divine bridegroom seeking out unfaithful Samaria to woo her back into covenant union, just as Hosea prophesied. He speaks gently to her and extends His loving mercy. As the ever-faithful husband, Jesus does not reject her but invites her to return to God’s kingdom.

At the same time, Jesus reminds her that “salvation is from the Jews” (Jn 4:22). This is a reference to God’s plan to save all humanity through the Davidic dynasty—a plan that the Samaritans rejected. The woman now realizes she is standing in the presence of a great prophet and asks Jesus about the Jewish belief in the coming of a savior from the line of David, a messiah-king. Jesus, the true son of David, replies, “I who speak to you am he” (Jn 2:26).

The woman comes to believe in Jesus and tells others of her great discovery. Many Samaritans begin to believe in Christ and thus return to their bridegroom (Jn 4:39-42). In this one scene, God Himself has come to draw this woman—and the estranged Samaritan people whom she represents—back to His heart. Jesus, the Jewish messiah, is the savior not only of the Jews but of all of Israel, including the Samaritans—no matter how far they have strayed.

To All the Nations

This inclusion of the Samaritans is just the first step of extending the Kingdom of David beyond the Jewish people. As Jesus begins to gather the lost sheep of Israel, we are reminded that the promises given to Abraham and David were not just for the twelve tribes of Israel but for the entire human family. We have seen throughout this study that God always intended to use the people of Israel and the kingdom of David as His instruments to gather back all the families of the earth into covenant union.

Thus, Jesus, at the beginning of His public ministry, reminds Israel of its universal mission, summoning the people to be the “light of the world” and the “salt of the earth” (Mt 5:13-14). He Himself consistently welcomes the sinners, covenant outcasts, and gentiles into His kingdom (see Mt 8:1-13, 9:9-13). He even praises the faith of a Roman centurion and the humility of a Syro-Phoenecian woman as more remarkable than the faith He has witnessed in Israel.

Indeed, His final act before ascending into heaven is to remind the Church of its worldwide mission: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Mt 28:19-20).

The Mission of the Church (Acts 1:8)

This mission of Jesus to the Jews, the Samaritans, and the gentiles is continued in the Church. In fact, the Book of Acts reveals the Church’s mission as a recapitulation of Christ’s public ministry.

Acts of the Apostles begins with a subtle but important point: “In the first book…I have dealt with all that Jesus began to do and teach” (Acts. 1:1). What is this “first book”? It is the Gospel of Luke, which covers Christ’s life from the incarnation to His ascension. Acts 1:1 reminds us, however, that Luke’s Gospel is just the start of what Jesus began to do and teach. In this second volume, known as the Acts of the Apostles, Luke will focus on what Jesus continues to do and teach through His Church. This highlights a fundamental principle: What Jesus did in His physical body two thousand years ago, He continues to do throughout history in His mystical body, the Church.

Just as Jesus had proclaimed His kingdom to Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and the gentiles, so now He commands His disciples to do the same. He tells them, “But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

This single verse serves as a table of contents for the evangelical mission of the early Church as outlined in Acts of the Apostles. The apostles, like their Master, will have the Holy Spirit descend upon them, and then they will preach the kingdom to the Jews. They begin their ministry in Jerusalem at Pentecost, sharing the Gospel of the King with Jews from all over the world (Acts 2). However, after persecution breaks out in Jerusalem, many Christians flee the city, and soon the Gospel spreads to Judea and then to Samaria, as multitudes outside Jerusalem are drawn into the Church (Acts 8).

After the conversion of Paul (Acts 9), he and the other Christian leaders take the Gospel of the Kingdom to the ends of the earth, moving outward through Asia Minor, Greece, and all the way to the heart of Roman Empire, the capital city of Rome itself. By the conclusion of Acts, we are told that Paul is there “preaching the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ quite openly and unhindered” (Acts 28:31).

Thus, at the end of Acts, this universal kingdom, which began with the mustard seed of Jesus’ life, is now firmly rooted in Rome under the leadership of Peter and Paul. Its branches have extended throughout the known world, through the witness of the apostles and those men they appointed to succeed them to gather all nations into the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. Indeed, God’s third promise to Abraham for a worldwide family is now being fulfilled through Jesus Christ and the Church He established.

Chapter 13 Discussion Guide

Matthew 3:1-17, 28:18-29, Genesis 3:18-19, Luke 22:44, John 19:2, 19:30, Acts 1:1

Please read aloud.

It’s difficult to imagine the sense of despair—and also hope—many Jews must have experienced in the first century. For most of the last 500 years, God’s people had been without a Davidic king, oppressed by various foreign powers and suffering like exiles in their own land. The Roman Empire represented the latest and fiercest of the regimes oppressing the Jewish people. Persecuted by the unprecedented force of Roman violence, taxation, and idolatry, the Jewish people were, on many levels, suffering as never before.

Nevertheless, against this backdrop of pain and misery, their expectation and desire for a restored kingdom and a messianic savior were reaching a fevered pitch. Enter John the Baptist:

Read Matthew 3:1-12.

1. Where is John Baptizing? What was important about that place in the story of salvation history? Why might this connection be significant?

Answer: John stands at the Jordan River, telling the people, “Repent!” Just as Joshua led the people through the wilderness to this very river and into the Promised Land centuries ago at the culmination of the first exodus, so now John leads the people to these same waters and invites them to a new and even greater exodus: an interior journey away from sin. He proclaims, “Repent…for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.”

Please read aloud.

The Old Testament prophets foretold that God would one day come to rescue His people from their oppressors and restore the great Davidic kingdom. They also depicted that restoration of Israel as a new exodus. It’s no wonder, then, that John’s message in the desert by the Jordan River (recalling the climax of the Exodus story) and his announcement about a great kingdom dawning (stirring the hopes about a future Davidic king) drew a lot of attention. Large crowds went out to follow him, hoping that the long-expected kingdom would soon arrive. Then, one day, it finally happens:

Read Matthew 3:13-17.

2. What does this passage tell us about Jesus’s identity? And what is the significance of this for the Jewish people?

Answer: As Jesus rises from the waters, the Spirit of God descends upon Him, and a heavenly voice speaks the words that signal His true identity: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (Mt 3:17). Indeed, now that Jesus is present, the kingdom of heaven is truly at hand.

Sidebar – The King

At the heart of Jesus’ public ministry, we find more than abstract principles about ethics or salvation. As king, Jesus’ mission is to restore the kingdom of David. Everywhere He goes, He preaches “the gospel of the kingdom” (Mt 4:23), which attracts people from all around the land (Mt 4:25). His famous Sermon on the Mount begins and ends with a message about the kingdom. Through His powerful healings, He is recognized as “the son of David,” the true king of the Jews. Much of His preaching and many of His parables elaborate upon this kingdom with various images: It is like a field, a treasure, a mustard seed, a pearl of great price. Clearly, Jesus is claiming to usher in a great kingdom. In the first-century Jewish context, practically everyone would understand that kingdom to be the promised restoration of the kingdom of David.

At a key turning point in His public ministry, Jesus calls His disciples to recognize that the central issue of this kingdom is His very identity. He asks the disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” In response, Peter declares, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Mt 16:16). The term “Christ” refers to the anointed messiah king whom the prophets foretold.

Peter is the first to refer explicitly to Jesus as the Christ, the messiah. In response to Peter’s faith, Jesus gives Him the keys of His kingdom:

“And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church and the powers of death shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” (Mt 16:18-19)

These keys of the kingdom symbolically represent one of the most important offices in the Davidic kingdom, the head of the royal household. In the Davidic dynasty of old, the king had a prime minister–like official who was vested with the king’s authority and who governed the day-to-day affairs of the kingdom. His office was symbolized by “the key of the house of David” (Is 22:22). With this background in mind, it becomes clear that, when Jesus the king gives Peter the keys of the kingdom, he is establishing him as the prime minister in the kingdom that He is establishing. It is no surprise that the Catholic Church sees this passage as shedding light on the papacy since it highlights the important leadership role Jesus gave to Peter (and those who succeed him in this office of prime minister) over the Church Christ founded.

Please read aloud.

Indeed, the kingdom is truly present in Jesus, but his kingdom will be established in a paradoxical manner. Despite His many Jewish followers, the rulers of the Jews reject Him, handing Him over to the Romans to be crucified. Yet it is through His death on that cross and His resurrection on the third day that Jesus saves His people and establishes the never-ending kingdom.

How does this occur? Let’s consider how all the covenants we have been studying—from Adam, Noah, and Abraham to Moses and David—converge on the cross and find their fulfillment there, shedding light on the meaning of Christ’s atoning sacrifice.

First, let’s look at Adam, and compare this with scenes from Jesus’s passion and death:

Read Genesis 3:18-19.

Read Luke 22:44, John 19:2, 19:30.

3. What connections do you see between what happens to Adam and these scenes in Christ’s life?

Answer: Jesus, as the new Adam, finds Himself in a garden (the Garden of Gethsemane) tested by the devil, but He proves to be a faithful Son (whereas Adam was unfaithful). He bore Adam’s curses—sweat, thorns, and death—by sweating blood, being crowned with thorns, and dying on the cross.

Please read aloud.

Now, let’s look at Noah. Consider these words from the Catechism:

To reunite all his children, scattered and led astray by sin, the Father willed to call the whole of humanity together into his Son’s Church. According to another image dear to the Church Fathers, she is prefigured by Noah’s ark, which alone saves from the flood.

4. How is Jesus like a new Noah? How does he save the world through his Church?

Answer: Like Noah, Jesus is a faithful son of Adam in the midst of a corrupt world. Like Noah, He offers salvation to His household, the family of God. Noah’s salvation came through the ark, which the Church Fathers saw as prefiguring the Church. Just as God used the ark to save Noah’s family from the flood, so does Christ save all humanity from sin through the Church He established by His death and resurrection.

Please read aloud.

Now, consider Abraham. Think back to the story of Abraham and Isaac, where Abraham is willing to offer his only son in sacrifice.

5. What parallels do you notice between Abraham’s story and Jesus? (See Genesis 22:1-19 for reference.)

Answer: Like Abraham’s only beloved son Isaac, Jesus, as the heavenly Father’s only beloved son, travels on a donkey to the ancient Mount Moriah, now in the city of Jerusalem, and bears the wood of sacrifice to Calvary in order to offer himself as a voluntary victim to atone for our sins and bring blessing to the entire world.

Please read aloud.

Now, let’s look at Moses.

6. How does Jesus provide for a “new exodus” and a “new Passover?” (See Exodus 12-13, for reference.)

Answer: Like Moses, who began the exodus from Egypt with the Passover, Jesus begins His passion—the work of the new exodus—with the Passover meal at the Last Supper. Just as the first Passover lambs were slain to spare the first-born Israelites in Egypt, so Jesus is sacrificed on the cross as the new Passover lamb, offering redemption to all humanity. And as the Passover was not just a sacrifice but a meal, all who participate in this new Passover are called to consume the flesh of the sacrificial lamb, Jesus Christ, in the Eucharist.

Please read aloud.

And most of all, in a paradoxical way, Jesus’ passion and death reveal His royal status as the true Davidic king. He is crowned, but with thorns; He is vested with a royal robe, but in mockery; He is hailed as a king by the soldiers, but in jest. His royal elevation is not to a throne, but to a cross with a simple sign above His head that reads, “Jesus the Nazorean, King of the Jews.” Though the Romans intended all this to mock Jesus’ royal claims, the Gospel writers highlight how they unwittingly reveal the truth: Jesus is, in fact, the true King of Kings.

7. How is Jesus’s crucifixion really Jesus’s moment of triumph?

Answer: While His crucifixion is seen by the world to be His moment of defeat, it is actually His moment of triumph over sin and death. His execution is actually His enthronement as He establishes His kingdom, the Church.

8. Looking at all the parallels, what stands out to you? What do you notice when you discover how Jesus fulfills the Old Testament? What implications does this have for your own understanding of the Bible and Christianity?

Allow the group to discuss.

Please read aloud.

Jesus clearly fulfills all the covenants God made to His people. However, God’s people are not just the Jews; like David himself, the messianic son of David is to reign over all of Israel, which originally consisted of all twelve tribes. As we saw in the previous chapter, the Jews, as the name suggests, are those Israelites who remained loyal to the divinely established Davidic dynasty in the southern kingdom of Judah. The ten northern tribes rebelled against their king and established their own kingdom, only to be invaded by the Assyrians in 722 B.C.—which became known as Samaria. In Jesus’s ministry, he also restores these lost ten tribes (Jn 4, see also Hosea 2).

But this is just the first step of extending the Kingdom of David beyond the Jewish people. As Jesus begins to gather the lost sheep of Israel, we are reminded that the promises given to Abraham and David were not just for the twelve tribes of Israel but for the entire human family. We have seen throughout this study that God always intended to use the people of Israel and the kingdom of David as His instruments to gather back all the families of the earth into covenant union.

Thus, Jesus, at the beginning of His public ministry, reminds Israel of its universal mission, summoning the people to be the “light of the world” and the “salt of the earth” (Mt 5:13-14). He Himself consistently welcomes the sinners, covenant outcasts, and gentiles into His kingdom (see Mt 8:1-13, 9:9-13). He even praises the faith of a Roman centurion and the humility of a Syro-Phoenecian woman as more remarkable than the faith He has witnessed in Israel.

Indeed, His final act before ascending into heaven is to remind the Church of its worldwide mission:

Read Matthew 28:18-20.

9. How does the Old Testament background give us a deeper understanding of the mission of the Church? What is Jesus commanding his disciples in this passage, and how does this fit with what God has been trying to do with his people from the beginning?

Allow the group to discuss.

Please read aloud.

This mission of Jesus to the Jews, the Samaritans, and the gentiles is continued in the Church. In fact, the Book of Acts reveals the Church’s mission as a recapitulation of Christ’s public ministry.

Read Acts 1:1.

10. Acts of the Apostles begins with a subtle but important point: “In the first book…I have dealt with all that Jesus began to do and teach” (Acts. 1:1). What is this “first book”?

Answer: It is the Gospel of Luke.

Please read aloud.

11. Acts 1:1 reminds us that Luke’s Gospel is just the start of what Jesus began to do and teach. What does the word “began” imply in this context? And what does this tell us about the Church?

Answer: In this second volume, known as the Acts of the Apostles, Luke will focus on what Jesus continues to do and teach through His Church. This highlights a fundamental principle: What Jesus did in His physical body two thousand years ago, He continues to do throughout history in His mystical body, the Church.

Please read aloud.

Indeed, just as Jesus had proclaimed His kingdom to Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and the gentiles, so now He commands His disciples to do the same. He tells them, “But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

This single verse serves as a table of contents for the evangelical mission of the early Church as outlined in Acts of the Apostles. The apostles, like their Master, they begin their ministry in Jerusalem, sharing the Gospel of the King with Jews from all over the world (Acts 2). Soon the Gospel spreads to Judea and then to Samaria, as multitudes outside Jerusalem are drawn into the Church (Acts 8). After the conversion of Paul (Acts 9), he and the other Christian leaders take the Gospel of the Kingdom to the ends of the earth, moving outward through Asia Minor, Greece, and all the way to the heart of Roman Empire, the capital city of Rome itself (Acts 28:31).

Thus, at the end of Acts, this universal kingdom, which began with the mustard seed of Jesus’ life, is now firmly rooted in Rome under the leadership of Peter and Paul. Its branches have extended throughout the known world, through the witness of the apostles and those men they appointed to succeed them to gather all nations into the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. Indeed, God’s third promise to Abraham for a worldwide family is now being fulfilled through Jesus Christ and the Church He established.

12. The Church is, in a certain sense, God’s plan from the beginning (see CCC 759). How does viewing the Church as the means by which God wants to bless the whole human family change the way you view it? And what does it mean for you, personally, to be included in this mission of the Church? How are you called to extend this blessing to others?

Allow the group to discuss.

13. We are now at the end of our study on salvation history. What did you think? What have you learned? How has God worked in your life throughout this study? What are you still pondering? And what are some next steps you hope to take in your understanding of the Scriptures and God’s plan for your life?

Allow the group to discuss.