Our journey through the big picture of the Bible now takes us to the Book of Exodus—a book that begins with a startling twist. On one hand, the Lord continues to work his covenantal plan for the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob even in the land of Egypt. The first chapter notes that the people were “fruitful” and “multiplied” (Ex 1:7), which recalls what the Bible said about Adam, Noah and the patriarchs. This underscores how the Israelites continue to share in the same blessing given to their forefathers. Indeed, the small tribe of seventy people that Jacob brought down to Egypt has now, hundreds of years later, “increased greatly” and become “exceedingly strong” (Ex 1:7).

On the other hand, Exodus introduces a new threat to God’s covenantal promises when it reports that a new king arises in Egypt “who did not know Joseph” (Ex 1:8).

This lack of “knowing” does not mean that the new Pharaoh was unacquainted with the famous dream interpreter, Joseph—the one who saved Egypt from famine and became Pharaoh’s chief administrator of the kingdom. Rather, in the politics of the day, the expression indicates a fundamental breach in Egypt’s stance toward Joseph’s family.

The term “to know” (yadah) in Hebrew signifies an intimate, covenant friendship with another person (see Gn 29:5, 2 Sm 7:2). The word can describe the profound communion an individual has with God (Ez 24:27, Is 1:3) and is even used as a euphemism for the most intimate union between a man and woman. When Adam knew his wife, she conceived a child (Gn 4:1).

Thus, Exodus 1:8 indicates that, with the rise of this new Pharaoh, Israel’s relationship with the Egyptians has been drastically ruptured. The new king does not “know” Joseph. This means the descendants of Jacob and Joseph no longer experience close covenant friendship with the Egyptian king. Instead of viewing the Israelites as an ally and a blessing, he views their increasing strength as a threat. He has them enslaved and attempts to destroy them by having every newborn male child thrown into the Nile River (Ex 1:8-21).

God responds to this crisis by sending His people Moses. The circumstances surrounding Moses’ birth have great significance, for they foreshadow his future vocation to rescue God’s people: Pharaoh’s daughter discovers the Hebrew child in a basket floating on the Nile, after his Israelite mother put him there in a desperate attempt to save the child’s life. The child is named “Moses,” which in Hebrew is derived from the verb mashah, meaning “to draw out of.” The one who was saved by being drawn out of the dangerous waters of the Nile will later rescue Israel by drawing the people out of Egypt through the waters of the Red Sea and leading them to the Promised Land.

Ten Strikes against Egypt’s Gods

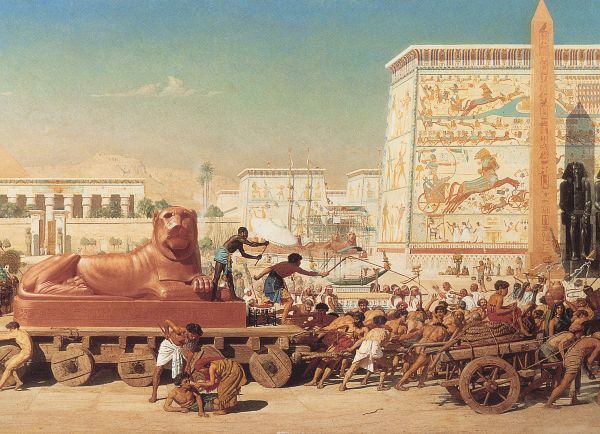

One of the most famous aspects of the Exodus story is that of the ten plagues that fall on Egypt. Though God (through Moses) commands Pharaoh to let His people go, the Egyptian king repeatedly refuses; as a result, his nation is afflicted by a series of plagues. At first glance, these plagues seem to be merely intended to make life miserable for the Egyptians and to serve as a punishment for their enslaving the Israelites. However, if we examine these divine acts of judgment in their historical context, we will see that they are also intended to help the Egyptians reject their pagan ways and embrace the one, true God.

First, note the theme of “knowing” in the account of Pharaoh and the plagues. When Moses first confronts Pharaoh with God’s command to release the people, the king responds, “Who is the Lord, that I should heed his voice and let Israel go? I do not know the Lord, and moreover I will not let Israel go” (Ex 5:2 emphasis added).

Recall how the word “know” refers to an intimate relationship: Right from the start, Pharaoh obstinately proclaims that he does not “know” the Lord and refuses to let the people go. Yet every time Pharaoh rejects God, his nation is confronted with another plague, whose purpose is to help the stubborn king overcome his lack of knowing the Lord. In fact, in almost every instance, Moses says each plague is given so that Pharaoh and the Egyptians may “know” the Lord (Ex 7:17; 8:10, 22; 9:29; 10:2). This refrain of knowing the Lord tells us that one of the main purposes of the plagues is to lead Egypt to know the one, true God—to recognize the supremacy of Yahweh.

But how do the plagues do this? These plagues are not random acts of retribution; they are strategic. Many scholars have pointed out that the ten plagues are connected with various Egyptian deities.

Sidebar – Egyptian Gods

For example, the Nile River, whose waters were a source of life in this region, was associated with various Egyptian gods. The god Osiris ruled the world, and the Nile represented his bloodstream. The Nile-god Hapy was a god of creation and fertility who was linked with the river’s annual inundation. There were even songs sung to the Nile, which itself was hailed as a deity: “Hail to thee, O Nile, that issues from the earth and comes to keep Egypt alive!”1 But in the first plague, when Moses strikes the Nile, it turns to blood, symbolizing judgment on the false gods associated with this river. In fact, all the plagues demonstrate superiority over the supposed gods of Egypt.

Similarly, the Egyptians worshipped the sun god Re, and in the ninth plague, the sun is darkened for three days, expressing Yahweh’s sovereignty over this supreme Egyptian deity. Underlying all of the plagues is a subversion of the Egyptian belief in Pharaoh himself as a god with power over the cosmos. According to Egyptian tradition, Pharaoh was responsible for ensuring that the land was fertile, that the Nile provided water, and that the sun shined its light. With this background, we can see how plagues bringing a darkened sun, destruction of crops, and a bloody, undrinkable, frog-infested Nile River would be a direct attack on Pharaoh’s divine attributes. They show that the God of Israel—not Pharaoh—is in control of the cosmos.

More than simply a display of God’s wrath, the plagues reveal the dominance of the God of Israel as He exercises divine judgment over the many false gods of the Egyptians (Ex 12:12). This is why God often says that the plagues are given so that “the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord” (Ex 7:5): Coming to know the Lord would involve recognizing the superiority of Yahweh and rejecting the Egyptian deities, who are powerless in the face of the God of Israel.

Not Forty Years

But the Egyptians are not the only people in the Book of Exodus who need to turn to God. A second key aspect of the Exodus story is the specific plan God has for Israel. It is often thought that God called Moses at the burning bush to lead Israel out of slavery and into the desert on their way to the Promised Land. However, if we take a closer look, we will see that God’s first concern is to liberate the people from a much deeper form of slavery than their drudgery under Egyptian taskmasters. Listen to what God tells Moses to say to Pharaoh:

You and the elders of Israel shall go to the king of Egypt and say to him, “The Lord, the God of the Hebrews, has met with us; and now, we pray you, let us go a three days’ journey into the wilderness, that we may sacrifice to the Lord our God.” (Ex 3:18)

Notice that the message to Pharaoh does not include anything about a permanent liberation, a forty-year journey through the wilderness, or Israel’s moving to the Promised Land. This initial request focuses on a short three-day journey, in which the Hebrews will worship God in the desert and then return to Egypt.

Certainly, God’s long-term goal is to bring Israel to the land originally promised to Abraham’s family (Gn 12:1-3, Ex 3:17). However, the initial need for a three-day journey to sacrifice in the desert may point to a deeper and more profound spiritual crisis in Israel than the problem slavery under Pharaoh. After the fourth plague, Pharaoh temporarily relents and says he will allow the Hebrews to sacrifice to their God, but they must do so within the land of Egypt. Moses responds by saying that this is not possible:

“It is not right to do so; for we shall sacrifice to the Lord our God offerings abominable to the Egyptians. If we sacrifice offerings abominable to the Egyptians before their eyes, will they not stone us? We must go three days’ journey into the wilderness and sacrificed to the Lord our God as he will command us.” (Ex 8:26-27)

Why does Israel need to go out into the wilderness to offer these sacrifices? And why would Moses be so nervous about offering them within the land of Egypt? Moreover, why would Moses say that the Egyptians will kill the Israelites if they see the people offering these particular sacrifices?

Moses is probably aware that the animals the Israelites intend to offer in sacrifice were associated with various Egyptian deities. Indeed, according to ancient Jewish interpretations (as well as many of the early Christian writers known as the Church Fathers), God commanded Israel to sacrifice the very animals that represented some of the most prominent gods in the Egyptian cult. For example, the sun goddess, Hathor, was depicted as a cow; the fertility god, Apis, as a bull; the gods Amun and Khnum as rams. Killing these animals that represented Egyptian deities would have been an abomination to the Egyptians.2 Such an action would have incited a riot and put the lives of the Israelites at risk. For this reason, Israel needed to go a three-day’s journey away from the Egyptians to sacrifice these animals in the solitude of the desert.

But why did God want Israel to sacrifice these animals in the first place? On a basic level, such an action expresses a rejection of the Egyptian deities associated with these animals. But there may be something more: The Bible reveals that, after hundreds of years of dwelling in the land of Egypt, the Israelites had not only been living with the Egyptians but also living like them, as Egyptian immorality and idolatry had crept into their hearts (see Jos 24:14, Ez 20:7-8). By instructing the people to sacrifice these animals, the Lord was, at least in part, challenging the people to acknowledge Him as the one true God and to renounce any lingering belief in the Egyptian deities represented by these animals. The three-day ceremony would provide the opportunity for the Israelites to repent and realign themselves with the covenant Yahweh established with their forefathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Here we see that God is not only trying to get Israel out of Egypt, He is also trying to get Egypt out of Israel.3

The Passover Choice

Even in the face of God’s mighty deeds, Pharaoh digs in his heels and refuses to let the people go to the wilderness to worship the Lord. God finally intervenes with one more plague that will be the impetus for the liberation of the people. In this tenth and most devastating plague, all the firstborn sons in Egypt will be killed, except those in households that celebrated a ritual called the Passover. The ritual involved sacrificing an unblemished lamb from their sheep or goats (Ex 12:5) and marking one’s doorpost with the blood of the lamb.

Think about how dangerous this would have been for the Israelites: The animals being sacrificed in the Passover—sheep and goats—were associated with Egyptian gods! We just saw how Moses did not want the people to sacrifice such animals in Egypt because he feared it would incite the Egyptians to kill them (Ex. 8:25-27). But now, with Pharaoh refusing to let the Israelites take leave, God commands them to sacrifice these animals right in the land of Egypt and then mark their doorposts with the sacrificial blood for all to see. The first Passover, therefore, involves a public renunciation of Egyptian idolatry that challenges the Israelites to make a decisive choice between serving the Lord or serving the Egyptian gods. It marks a key turning point away from their past and starting anew with Yahweh.

Out of Egypt

Imagine the grief and terror of the Egyptians the following morning when they awoke to find all the first born sons in Egypt dead, except those sons of the Israelites who had celebrated the Passover the night before. Pharaoh finally relents and lets the people go without any conditions. He drives them from the land, saying, “Go, serve the Lord, as you have said. Take your flocks and your herds, as you have said and be gone” (Ex 12:32).

Yet shortly after the Israelites are leaving, Pharaoh has a change of heart. He sends his army after the Israelites, which chases the people all the way to the Red Sea. This sets the stage for one of God’s greatest acts in the Old Testament, one that will serve as a paradigm for all future saving acts of God: the miraculous parting of the sea. With Israel backed up against the Red Sea and no way of escape, Moses miraculously divides the waters so that the people can pass to the other side. When Pharaoh and his army try to follow the Israelites, the waters collapse upon them and they are killed. Israel is definitively freed from the Egyptians.

Coming to Know the Lord

Looking back now on the strife between Moses and Pharaoh, we can see that the plagues did begin to fulfill their purpose, as some of the Egyptians at least came to see the supreme power of Israel’s God. After the third plague of the gnats, Pharaoh’s own magicians, for example, admit to the king, “This is the finger of God” (Ex 8:19). With the announcement of the seventh plague involving hail, some of Pharaoh’s servants are described as “fearing the word of the Lord” and acting to protect their cattle and slaves from the impending punishment (Ex 9:20). After the eighth plague of the locusts, Pharaoh’s servants beg him to let the people go: “Let the men go, that they may serve the Lord their God; do you not yet understand that Egypt is ruined?” (Ex 10:7).

This movement toward recognizing the supreme power of Yahweh reached a peak after the death of the firstborns, when many in Egypt joined themselves to the Israelites and followed Moses out of Egypt (Ex 12:38)—a significant turn of events that points to Israel’s ultimate vocation to gather the nations into covenant with God.

The Chosen People?

Even though the people have witnessed so many miraculous manifestations of God’s power, life on pilgrimage is not easy. In their hurried escape, the people have fled Egypt without adequate provisions for food or water—a significant concern for a large group of hundreds of thousands of people traveling in the desert. Nevertheless, God continues to care for their daily needs, miraculously providing them with heavenly bread (called manna) for food and the water from a rock (see Ex 16-17) as they make their way toward the Promised Land.

At Mount Sinai, God will give the Israelites the Ten Commandments and re-establish them as His covenant people. But first, the Lord reveals more of His plan for Israel—a plan that entails much more than giving them the Promised Land. God shares His vision and calling for the nation of Israel in a key passage that serves as a mission statement for God’s people:

“Now therefore, if you will obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my own possession among all peoples; for all the earth is mine, and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.” (Ex 19:6)

This is an important passage that sheds light on why Israel is sometimes called “the chosen people.” From a modern Western perspective, this designation might seem unfair. Why would God “choose” one group of people and not another? Why does God give to Israel Moses, the law, the prophets, and the covenant and not to the other nations?.

But this passage helps us see that God does not choose Israel instead of the rest of the world; He chooses Israel for the sake of the rest of the world.4 God always had the entire human family in mind when He raised Israel up to be His covenantal people. From the very beginning, God intended the descendants of Abraham to be His instrument for bringing blessing to all the nations (Gn 12:3, 22:18).

At Mount Sinai, God now elaborates on this universal mission by referring to Israel as a “kingdom of priests.” This indicates that God’s people are called to be a great kingdom, but one with a priestly ministry to the world. Israel is called to act as God’s representative to the other nations, leading them, like a priest, to worship the one, true God. In fact, this priestly mission to the nations fits God’s motivation in the preceding verse: “For all the earth is mine,” God said (Ex 19:5). God’s particular call for Israel has a universal scope. Israel is to be a “kingdom of priests” for the sake of the rest of the world—“for all the earth is mine,” says the Lord.

This royal priestly mission also may be reflected in God’s designation of Israel as his “first born son” (Exodus 4:22). Recall from the previous chapter how the father in ancient Israel possessed a kingly and priestly role in the family that was passed on to the firstborn by means of a blessing. If Israel were called God’s “first-born son” (Ex 4:22), it is fitting that Israel would also be seen as a kingdom of priests (Ex 19:6). Like a firstborn son in a household, Israel, as God’s first-born son in the family of nations, appropriately has a kingly and priestly mission to the other members of God’s family, the other nations. Indeed, Israel is the bearer of the covenant blessings for the whole world. The question will be: How well will Israel live up to this high calling?

Discussion Guide – Chapter 7

Exodus 1:8-14; 2:1-10; 3:13-20; 5:1-2; 7:17-18; 12:1-13; 19:3-6

Please read aloud.

Our journey through the big picture of the Bible now takes us to the Book of Exodus—a book that begins with a startling twist. A new king has arisen in Egypt “who did not know Joseph” (Ex 1:8).

Read Exodus 1: 8-14

- What might it mean that Pharaoh did not “know” Joseph? (Ex. 1:8) Did the new Pharaoh really not know who Joseph was?

Answer: We read that there is a new king in Egypt – one who does not “know” Joseph. This lack of “knowing” does not mean that the new Pharaoh was unacquainted with the famous dream interpreter, Joseph. Rather, in the politics of the day, the expression indicated a fundamental breach in Egypt’s stance toward Joseph’s family. The term “to know” (yadah, in Hebrew) signifies an intimate, covenant friendship with another person. Thus, Exodus 1:8 indicates that, with the rise of this new Pharaoh, Israel’s relationship with the Egyptians has been drastically ruptured. Out of fear that the Israelites might continue to multiply and thus grow too powerful, Pharaoh has not only subjected the Israelites to lives of hard service but has even gone so far as to command that all sons born to the Hebrews be thrown into the Nile (Ex. 1:21).

2. What might it mean that the Israelites were made to “serve” (Hebrew: Avad)? (Ex. 1:14)

Answer: While the term “serve” is indeed used to describe the physical toil and labor of the Israelites, the word has a second and very important meaning. “Avad”, the Hebrew word for “serve”, connotes both work and worship. Therefore, the Israelites were not only held captive physically, but spiritually as well. This theme of freedom to worship is critical for understanding the Exodus narrative.

Please read aloud.

This is going to be an important thing to keep in mind throughout this study. The Exodus is not simply about getting Israel out of Egypt, but also about getting Egypt (and its idolatry) out of Israel.

The story continues with the person of Moses. Let’s read a bit more about him:

Read Exodus 2: 1-10

3. What does Moses’ name mean? Why does he have this name, and how might this foreshadow his role in the story?

Answer: The circumstances surrounding Moses’ birth have great significance, for they foreshadow his future vocation to rescue God’s people: Pharaoh’s daughter discovers the Hebrew child in a basket floating on the Nile, after his Israelite mother put him there in a desperate attempt to save the child’s life. The child is named “Moses,” which in Hebrew is derived from the verb mashah, meaning “to draw out of.” The one who was saved by being drawn out of the dangerous waters of the Nile will later rescue Israel by drawing the people out of Egypt through the waters of the Red Sea and leading them to the Promised Land.

Please read aloud.

There is so much that happens in Moses’ story—more than we could fully cover in this chapter. But when Moses has grown up, he flees to Midian after an altercation with an Egyptian. It is there, at Mount Horeb, that he encounters God in the burning bush. This is a key moment for understanding Moses’ role in Salvation History:

Read Exodus 3: 13-20

4. What does God initially tell Moses to ask of Pharaoh? (See Ex. 3:18). Why is this important?

Answer: God tells Moses to ask permission for the Israelites to take a three days’ journey into the wilderness to sacrifice to the Lord. It is often thought that God called Moses at the burning bush to lead Israel out of slavery and into the desert on their way to the Promised Land. However, God’s first concern is to liberate the people from a much deeper form of slavery than their drudgery under Egyptian taskmasters. The initial need for a three-day journey to sacrifice in the desert points to a deeper and more profound spiritual crisis in Israel than the problem of slavery under Pharaoh.

5. Later in the story, Moses will tell Pharaoh that the Israelites cannot sacrifice to God in Egypt for fear of being stoned by the Egyptians. Why do you think Israel needs to go into the wilderness in order to safely offer sacrifices to God? (Hint: recall the meaning of the term “avad” discussed earlier).

Answer: The animals the Israelites intended to offer in sacrifice were associated with various Egyptian deities. Indeed, God commanded Israel to sacrifice the very animals that represented some of the most prominent gods in the Egyptian cult. For example, the sun goddess, Hathor, was depicted as a cow; the fertility god, Apis, as a bull; the gods Amun and Khnum as rams. Killing these animals that represented Egyptian deities would have been an abomination to the Egyptians.5 Such an action would have incited a riot and put the lives of the Israelites at risk. For this reason, Israel needed to go a three-day’s journey away from the Egyptians to sacrifice these animals in the solitude of the desert.

6. Given the relationship between these animals and Egyptian gods, why do you think God wanted Israel to sacrifice these animals in the first place?

Answer: On a basic level, such an action expresses a rejection of the Egyptian deities associated with these animals. But there may be something more: The Bible reveals that, after hundreds of years of dwelling in the land of Egypt, the Israelites had not only been living with the Egyptians but also living like them, as Egyptian immorality and idolatry had crept into their hearts (see Jos 24:14, Ez 20:7-8). By instructing the people to sacrifice these animals, the Lord was challenging the people to acknowledge Him as the one true God and to renounce any lingering belief in the Egyptian deities represented by these animals. The three-day ceremony would provide the opportunity for the Israelites to repent and realign themselves with the covenant Yahweh established with their forefathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Here we see that God is not only trying to get Israel out of Egypt, He is also trying to get Egypt out of Israel.6

7. What are some of the “pagan gods” of the culture we live in? (Some examples might be success, popularity, fitness, education, or technology). How can these things become idols in our lives? In what ways could we “sacrifice” these idols?

Allow the group to discuss.

Please read aloud.

We now move onto one of the most famous parts of the narrative: the ten plagues. At first glance, these plagues seem to be merely intended to make life miserable for the Egyptians and to serve as a punishment for their enslaving the Israelites. However, if we examine these divine acts of judgment in their historical context, we will see that they are also intended to help the Egyptians reject their pagan ways and embrace the one, true God.

Read Exodus 5:1-2 and 7:17-18

8. Based on your reading of these passages, what do you think is the purpose of the plagues? (Hint: recall the earlier discussion of the term “yadah”).

Answer: Note the theme of “knowing” in the account of Pharaoh and the plagues. Right from the start, Pharaoh obstinately proclaims that he does not “know” the Lord and refuses to let the people go. Yet every time Pharaoh rejects God, his nation is confronted with another plague, whose purpose is to help the stubborn king overcome his lack of knowing the Lord. In fact, in almost every instance, Moses says each plague is given so that Pharaoh and the Egyptians may “know” the Lord (Ex 7:17; 8:10, 22; 9:29; 10:2). This refrain of knowing the Lord tells us that one of the main purposes of the plagues is to lead Egypt to know the one, true God—to recognize the supremacy of Yahweh. In fact, the plagues themselves can be seen as judgement on the Egyptian gods, and an invitation to come to know the Lord (see sidebar).

Sidebar – Egyptian Gods

9. Why do you think God chose the specific plagues he did? Are they random, or is there some significance to them?

Answer: Many scholars have pointed out that the ten plagues are connected with various Egyptian deities. For example, the Nile River, whose waters were a source of life in this region, was associated with various Egyptian gods. The god Osiris ruled the world, and the Nile represented his bloodstream. The Nile-god Hapy was a god of creation and fertility who was linked with the river’s annual inundation. There were even songs sung to the Nile, which itself was hailed as a deity: “Hail to thee, O Nile, that issues from the earth and comes to keep Egypt alive!”7 But in the first plague, when Moses strikes the Nile, it turns to blood, symbolizing judgment on the false gods associated with this river.

Similarly, the Egyptians worshipped the sun god Re, and in the ninth plague, the sun is darkened for three days, expressing Yahweh’s sovereignty over this supreme Egyptian deity. Underlying all of the plagues is a subversion of the Egyptian belief in Pharaoh himself as a god with power over the cosmos. According to Egyptian tradition, Pharaoh was responsible for ensuring that the land was fertile, that the Nile provided water, and that the sun shined its light. With this background, we can see how plagues bringing a darkened sun, destruction of crops, and a bloody, undrinkable, frog-infested Nile River would be a direct attack on Pharaoh’s divine attributes. They show that the God of Israel—not Pharaoh—is in control of the cosmos.

10. Based on this background, how would you summarize the purpose of the plagues?

Answer: Allow the group to discuss. Additionally: More than simply a display of God’s wrath, the plagues reveal the dominance of the God of Israel as He exercises divine judgment over the many false gods of the Egyptians (Ex 12:12). This is why God often says that the plagues are given so that “the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord” (Ex 7:5): Coming to know the Lord would involve recognizing the superiority of Yahweh and rejecting the Egyptian deities, who are powerless in the face of the God of Israel.

Please read aloud.

This leads us to the next major event in the narrative: the institution of Passover.

Read Exodus 12:1-13

Please read aloud.

In this tenth and most devastating plague, all the firstborn sons in Egypt will be killed, except those in households that celebrated a ritual called the Passover. The ritual involved sacrificing an unblemished lamb from their sheep or goats (Ex 12:5) and marking one’s doorpost with the blood of the lamb.

Think about how dangerous this would have been for the Israelites: The animals being sacrificed in the Passover—sheep and goats—were associated with Egyptian gods. We just saw how Moses did not want the people to sacrifice such animals in Egypt because he feared it would incite the Egyptians to kill them (Ex. 8:25-27). But now, with Pharaoh refusing to let the Israelites take leave, God commands them to sacrifice these animals right in the land of Egypt and then mark their doorposts with the sacrificial blood for all to see. The first Passover, therefore, involves a public renunciation of Egyptian idolatry that challenges the Israelites to make a decisive choice between serving the Lord or serving the Egyptian gods. It marks a key turning point away from their past and starting anew with Yahweh.

11. The Passover was a bold challenge to the Israelites to make their faith public in a hostile environment. How does this challenge relate to us as Christians today? Have you ever felt like God was calling you to display your faith publicly though you knew it might not be well-received? How did it turn out?

Answer: Allow the group to discuss.

Please read aloud.

Imagine the grief and terror of the Egyptians the following morning when they awoke to find all the first born sons in Egypt dead, except those sons of the Israelites who had celebrated the Passover the night before. Pharaoh finally relents and lets the people go without any conditions. Yet shortly after the Israelites leave, Pharaoh has a change of heart. He sends his army after the Israelites, which chases the people all the way to the Red Sea. With Israel backed up against the Red Sea and no way of escape, Moses miraculously divides the waters so that the people can pass to the other side. When Pharaoh and his army try to follow the Israelites, the waters collapse upon them and they are killed. Israel is definitively freed from the Egyptians.

12. Do you think the plagues achieved their purpose of helping the Egyptians to know the one, true God?

Answer: Looking back now on the strife between Moses and Pharaoh, we can see that the plagues did begin to fulfill their purpose, as some of the Egyptians at least came to see the supreme power of Israel’s God. (See Ex 8:19; Ex 9:20; Ex 10:7). This movement toward recognizing the supreme power of Yahweh reached a peak after the death of the firstborns, when many in Egypt joined themselves to the Israelites and followed Moses out of Egypt (Ex 12:38)—a significant turn of events that points to Israel’s ultimate vocation to gather all the nations into covenant with God.

Please read aloud.

This is a momentous moment; however, it is only the beginning for the people of Israel. It is in the midst of their desert wanderings that Yahweh reveals to the Israelites the next step of his plan for his chosen people – a plan that entails much more than giving them the Promised Land. God shares His vision and calling for the nation of Israel in a key passage that serves as a mission statement for God’s people.

Read Exodus 19:3-6

13. In this passage, the Israelites are referred to as God’s “own possession” and a “kingdom of priests.” In other places they are referred to as God’s “chosen people.” What might these designations mean?

Answer: From a modern, Western perspective, the designation “chosen people” might seem unfair. Why would God “choose” one group of people, and not another, to receive the law, the prophets, and the covenant? This passage helps us see that God does not choose Israel instead of the rest of the world; He chooses Israel for the sake of the rest of the world.8 God always had the entire human family in mind when He raised Israel up to be His covenantal people. From the very beginning, God intended the descendants of Abraham to be His instrument for bringing blessing to all the nations (Gn 12:3, 22:18).

At Mount Sinai, God elaborates on this universal mission by referring to Israel as a “kingdom of priests.” This indicates that God’s people are called to be a great kingdom, but one with a priestly ministry to the world. Israel is called to act as God’s representative to the other nations, leading them, like a priest, to worship the one, true God.

14. God’s many gifts to his chosen people (the law, the prophets, the covenant) were meant to be used by Israel to bring all nations into relationship with God. What gifts has God given you? How might God be “choosing” you to use these gifts to serve him?